Anger at overdraft fees gets hotter, bigger and louder

By Kathy ChuUSA TODAY 9/29/09

Controversial bank account fees, which have fattened banks’ bottom linesat the expense of vulnerable consumers, are rapidly becoming a black eye for the industry.

Undersiege are the fees charged to consumers who spend more than they have in theiraccounts, whether by check, debit card or at the ATM. Lastweek, four of the nation’s largest banks said they would scale back some oftheir overdraft policies. Their efforts, while meaningful, have

Bankshave done this by covering debit card transactions as small as $1 and charging a fee as high as$35. Some also charge fees before consumers overdraw by deducting a purchasewhen it’s made, instead of when it clears. And they’ve processed transactionsfrom highest to lowest dollar amount — which empties

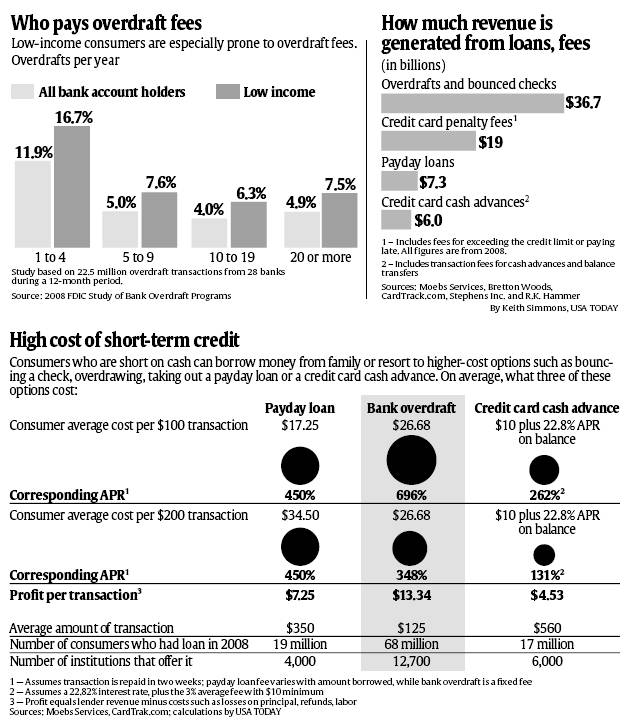

Ironically, the changes banks have made to their overdraft policies areonly fueling calls to reform the entire industry. Overdraft coverage can beless regulated and cost more than other high-cost (and equally criticized)options, including payday loans, in an estimated $70 billion short-term creditmarket. On average, consumers will pay a fee of $26.68 ev-

“Whenconsumers (overdraw) recurrently, it is a credit product, and they’re paying eye-popping rates,”says Sheila Bair, Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. chair, who is pushing forbanks to get consumers’ permission before covering overdrafts, for a fee, andto disclose APRs. Bankshave long said thatcustomers appreciate automatic overdraft coverage and that this service helpsconsumers avoid the embarrassment of a declined transaction. But they’re nowacknowledging these fees can push consumers into distress.

Startingnext year, Chase won’t pay debit card overdrafts and charge a fee withoutconsumers’ consent. Bank of America is reducing the maximum number of dailyoverdraft fees consumers could be hit with, from 10 to four, and lettingcustomers opt out of this coverage. “We’ve seen that the overdraft fees havebecome a bigger problem for customers,” says Brian Moynihan, president ofBofA’s consumer and small-business banking group.

TamTran, 36, of Columbia, Md., has paid BofA more than $5,000 in overdraft fees inthe past year. In 18years with the bank, Tran says he’s never had problems managing his money. Butwhen his father went into the hospital, overdraft fees piled up forsmall-dollar debit card items. He repeatedly asked the bank not to approvetransactions he didn’t have money for and to stop clearing them from high tolow dollar amount, but BofA kept doing so. The bank said it approved histransactions because he had been a “good customer,” he says.

‘Trappedin debt’

Throughthe years, banks’ high overdraft fees have become marketing fodder for paydaylenders.

Thesmaller the overdraft, the higher the APR. On a median debit card overdraft of$20, in which the lender charges a fee of $27, the APR translates to 3,520%, ifthe credit is paid back in two weeks, says a 2008 FDIC report. Payday loans,meanwhile, carry an APR of 391% to 449%, assuming a $15 to $17.25 fee per $100borrowed. Yet,payday loans can cost more than overdraft fees on large-dollar transactions.For instance, if a consumer overdraws by $200, they’d pay the same $27 fee (a348% APR), but if they borrowed the same amount from a payday lender, they’dhave to pay an average $34.50 fee (a 450% APR), Moebs Services says. MichaelMoebs, the founder of Moebs Services, cautions that “at the low end of any loanamount, we’re going to see very high APRs.” He also points out that paydayloans and overdraft coverage can cost less than the alternative. Averagebounced-check fees charged by the merchant and bank total $53.62, he says.

RichardHunt, president of the Consumer Bankers Association, says payday loans andoverdrafts are a “day and night comparison.” The first may cater to lesscreditworthy consumers, he says, while the other is a “service” to those whomake a mistake. Research released in 2007 by Marc Fusaro, then an assistanteconomics professor at East Carolina University in Greenville, N.C., finds that79% of consumers who overdraw bank accounts do so by mistake. The other 21% areoverdrawing because they need credit. Advocates say consumers who need short-term credit should considerborrowing from family or finding cheaper alternatives, such as a line ofcredit. Those who use payday loans or overdraw risk getting mired in debt, theynote.

“Bothindustries are completely dependent on borrowers trapped in debt to generatemost of their revenue,” says Eric Halperin, director of the Center forResponsible Lending’s Washington office. Manyborrowers can’t pay back the payday loan with a single paycheck, but lendersstill debit their bank account for the total due, possibly triggering bouncedchecks or overdrafts, says Jean Ann Fox of the Consumer Federation of America.

The FDICis working to find affordable alternatives to payday loans and overdrafts. Asmall-dollar loan program launched in 2008 has shown that “banks can providelower-cost loans in a way that is profitable and more responsible,” Bair says.The problem is that banksmay be reluctant to “cannibalize” on their overdraft fee income with lower-costloans, Bair wrote in a 2005 report when she taught at the University ofMassachusetts-Amherst. ProbityFinancial Services of Austin is offering an alternative to high overdraft fees:It’s partnering with a small bank to offer a checking account that, for a$19.95 monthly fee, allows consumers to overdraw by as much as $500, but won’tcharge them a fee each time they do so.

Bankchanges ‘fall well short’

Fusaro’sresearch feeds a frenzied debate about whether overdraft coverage should beregulated as loans and subject to an APR, similar to what’s imposed on paydayloans. Even though banking regulators have acknowledged that overdraft coverageis a form of credit, Fusaro believes it would be “misguided” to regulate themas loans. Nevertheless, consumer advocates are clamoring for tighter restrictionson payday loans and overdrafts, such as a 36% interest rate cap. They also wantbanks to disclose APRs on overdraft products so consumers can compare theiroptions. Halperinsays that banks’ recent changes to their overdraft policies, while animprovement, “fall well short of providing full protection for consumers.”

Rep.Carolyn Maloney, D-N.Y., sponsored a bill she believes will give all bankcustomers “strong and consistent protections from deceptive overdraftpolicies.” It would require banks to get consumers’ permission to pay anoverdraft, and charge a fee, and clear transactions in chronological order.

Thisagency is needed, says Elizabeth Warren, a Harvard law professor, because withfinancial products, “where it’s possible to change the agreements by includingan extra piece of paper stuffed in a bill, the industry will constantly reshapethe terms.” “WhenCongress outlaws one practice, the industry just moves to a practice thataccomplishes the same thing,” adds Warren, who chairs the CongressionalOversight Panel, created by Congress last year to study how financialinstitutions’ actions affect the economy. “It’s like hammering fence posts inan open field: It’s easy to get around them.” Bankshave already found ways to minimize the impact of credit card reform passedearlier this year by Congress. Even before the ink was dry on the law, banksraised rates for a broad spectrum of new and existing credit card borrowers. In the first twoquarters of 2009, the lowest advertised credit card rates rose by 20%, even asbanks’ funding costs declined, Pew Charitable Trusts says.

Tranfeels it’s not enough for banks to do “damage control” by changing someoverdraft policies. Regulators, he says, have to address a systemic problemwhere banks will charge unsuspecting consumers as many overdraft fees aspossible. Banks, he says, have “gone too far.”

By H. DarrBeiser, USA TODAY