By David Quammen

Originially published in the National Geographic Magazine in the January 2009 issue.

By David Quammen

Originially published in the National Geographic Magazine in the January 2009 issue.

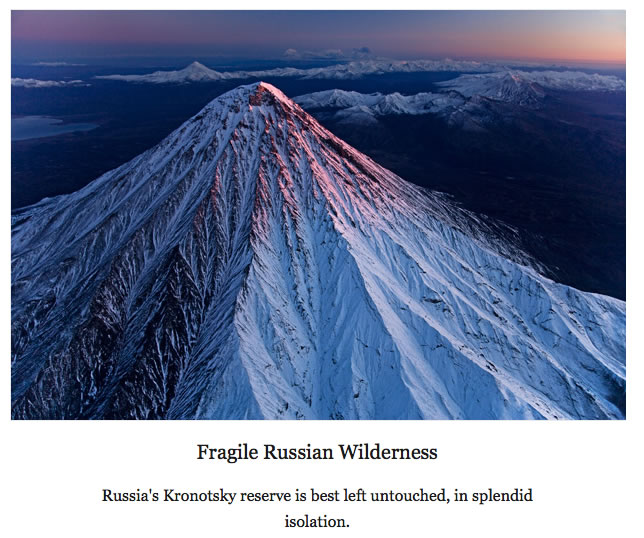

Some places on this planet are so wondrous, and so frangible, that maybe we just shouldn't go there.

Maybe we should leave them alone and appreciate them from afar. Send a delegated observer who will absorb much, walk lightly, and report back as Neil Armstrong did from the moon—and let the rest of us stay home. That paradox applies to Kronotsky Zapovednik, a remote nature reserve on the east side of Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula, along the Pacific coast a thousand miles north of Japan. It's a splendorous landscape, dynamic and rich, tumultuous and delicate, encompassing 2.8 million acres of volcanic mountains and forest and tundra and river bottoms as well as more than 700 brown bears, thickets of Siberian dwarf pine (with edible nuts for the bears) and relict "graceful" fir (Abies sachalinensis) left in the wake of Pleistocene glaciers, a major rookery of Steller sea lions on the coast, a population of kokanee salmon in Kronotskoye Lake, along with sea-run salmon and steelhead in the rivers, eagles and gyrfalcons and wolverines and many other species—terrain altogether too good to be a mere destination. With so much to offer, so much at stake, so much that can be quickly damaged but (because of the high latitudes, the slow growth of plants, the intricacies of its geothermal underpinnings, the specialness of its ecosystems, the delicacy of its topographic repose) not quickly repaired, does Kronotsky need people, even as visitors? I raise this question, acutely aware that it may sound hypocritical, or anyway inconsistent, given that I've recently left my own boot prints in Kronotsky's yielding crust.

The government of Russia recognizes such spectacular fragility with that categorical zapovednik, connoting roughly this: "a restricted zone, set aside for the study and protection of flora and fauna and geology; tourism limited or forbidden; thanks for your interest, but go away." It's a farsighted sort of statutory designation, bravely and judiciously antidemocratic in a country where antidemocracy has a long, brutal history. Scientists are permitted to enter zapovedniks, though only for research and under stringent conditions. Kronotsky is one of 101 such reserves in Russia, by the latest count, and was among the first, decreed in 1934. Before that it had been a sable refuge, established in 1882 at the prompting of local people, hunters and trappers who valued the forests surrounding Kronotskoye Lake as prime habitat for Martes zibellina, the sable. The Kamchatka Peninsula is very distant from Moscow (as distant, in fact, as Moscow is from Boston), and to Joseph Stalin's Soviet government in the mid-1930s (with much else on its agenda) the opportunity costs of putting a modest chunk of that wilderness within protective boundaries probably didn't seem high. In 1941 a second kind of asset revealed itself within the reserve, when a hydrologist named Tatiana I. Ustinova discovered geysers there.

In the cold springtime of that year, Ustinova and her guide were exploring the headwaters of the Shumnaya River by dogsled. They paused near a confluence point and happened to notice, at some distance along the water's edge, a large outburst of steam. With hungry dogs and other urgencies pulling her away, Ustinova wasn't able to see much more, not then, but she returned several months later to map and study what proved to be a whole complex of geothermal features, including about 40 geysers. She named her first geyser Pervenets, meaning "firstborn." The tributary she ascended is now called the Geysernaya River, and above one of its bends is a slope known as Vitrazh, or stained glass, for its multicolored residue from a score of large and small vents. Kronotsky's Dolina Geyserov (Valley of Geysers) took its place as one of the world's major geyser areas, in a league with Yellowstone, El Tatio in Chile, Waiotapu on New Zealand's North Island, and Iceland.

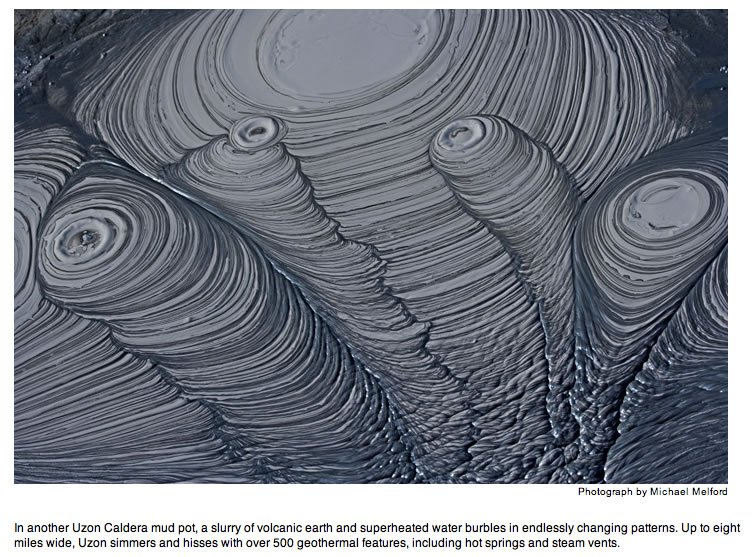

Geysers are generally associated with volcanic activity, and that's certainly the case in Kronotsky. Kamchatka as a whole is abundantly pustulated with volcanoes, of which about two dozen, including some inactive ones, lie within the zapovednik or along its borders. Kronotsky Volcano is the tallest, a perfect cone rising to 11,552 feet. Krasheninnikov Volcano (named for Stepan Petrovich Krasheninnikov, a hardy naturalist who explored Kamchatka in the early 18th century) is its nonidentical twin, lying just southwestward across the Kronotskaya River. Still farther southwest is what would be, but no longer is, the third in a huge three-peak sequence. Instead of a high cone, it's a broad, low bowl, up to eight miles in diameter, filled with fumaroles and hot springs and sulfurous lakes, blueberry-and-heather tundra, forest patches of birch and Siberian dwarf pine, all rimmed by a circular ridge left behind when a vast volcano blasted itself open about 40,000 years ago. The bowl is called Uzon Caldera. Its name comes from the kindly spirit Uzon, a powerful figure in the legends of the native Koryak people. The exploration and study of Uzon Caldera by scientists, as well as Ustinova's finding of the Valley of Geysers, gave additional purpose to the zapovednik: protecting geological wonders as well as biological ones.

The story told by Koryaks about Uzon and his caldera has the ring of a parable. He was a friend to humanity, quieting earth tremors, stifling volcanic eruptions with his hands, doing other good deeds; but he endured a lonely existence, living secretively atop his own mountain so that evil spirits wouldn't come and destroy the place. Then he fell in love. She was a human—a beautiful girl named Nayun, with eyes like stars, lips like cranberries, eyebrows as dark and glossy as two sables. She loved Uzon in return, and he took her away to his mountain. So far, so good. But after some years of marital bliss and isolation, Nayun began to pine for her human relatives. Couldn't she have a visit with them somehow? Uzon, wanting to please her, made a desperate and tragic mistake: He spread the mountains with his mighty arms and created a road. People came, curious and disruptive. Now everybody knew Uzon's secret hideaway, including those evil spirits. "The earth yawned with a horrible crash having absorbed a huge mountain," in one telling of this tale, by G. A. Karpov, "and mighty Uzon turned into stone forever." You can see him there even today, petrified into a high peak on the northwestern perimeter of the caldera, his head bowed, his arms stretched around to form the rim.

If you do see him, you'll be among the few. The ban against tourism has been relaxed, but not much, for Kronotsky. About 3,000 nonscientific visitors now enter each year, and of those, only half make a stop in Uzon Caldera. Regulations limit the number, but so do logistics, lack of infrastructure, and cost. For starters, there is no road into Kronotsky Zapovednik from the more settled parts (which are not very settled) of Kamchatka. No roads within the reserve either, notwithstanding the legend of Uzon. The in-and-out transport consists mainly of Mi-8 helicopters, thunderously powerful machines such as once ferried troops for the Soviet Army. Sitting in an Mi-8 as it powers up for takeoff, strapped into a rickety seat beside a porthole window, you feel as you would in a crowded school bus with a sizable sawmill bolted to its roof—until the whole thing levitates. Tourist flights leave from a heliport 20 miles from Petropavlovsk, Kamchatka's capital, and are permitted to land only on helipads in the caldera and the Valley of Geysers. Neither place offers overnight accommodation for tourists, so a visit to the reserve constitutes a very pricey ($700) day trip with lunch. The customer traffic seems mostly made up of wealthy Russians, Europeans on adventuresome holidays, and the occasional American. Five hours in Kronotsky isn't something that ordinary families in Petropavlovsk could normally afford; it's not like loading the kids into the van for a summer trip that includes an ice cream cone at Old Faithful. Choppering in to see geysers and volcanoes and maybe a few brown bears (fleeing across the tundra as your pilot hazes them at low elevation to provide a good look) is nature appreciation for the affluent, sedentary elite. It's dramatic and thrilling and privileged and rude. It makes me dyspeptic, but?…?how would I know that if I hadn't been there and done it myself?

The authorities who manage Kronotsky and the scientists who study it are sensitive to the downside of such tourism. Everybody leaves a footprint of some sort, the crucial questions being how deep and how many. At the beginning and the end of each summer season, investigators look for impacts at the caldera and the geysers. Their report helps inform decisions about the next season's visitation limits and dates. But the greater conundrum of Kronotsky, the one that provokes thought and not just sour belly, is how the concern over human-caused degradation should be reconciled with the inherent, violent dynamism of the place. This conundrum came to a point on June 3, 2007, when a massive wall of rock, mud, clay, and sand broke loose from a high ridge and slid, roaring, down a small creek valley, obliterating a hundred-foot waterfall, damming the Geysernaya River (all in a matter of seconds), and burying much of the Valley of Geysers beneath the resulting new lake. George Patton's army, marching through in hobnailed boots, couldn't have made such a mess.

Pervenets, Ustinova's firstborn geyser, is gone. So are a few other famous spouts. The rest remain. Vitrazh, the stained-glass mosaic, is intact. Alarming reports reached the international press, vacations were canceled, and people immediately disagreed about whether the slide was a tragedy or simply a fascinating natural shrug. "We scientists believe we are quite lucky to witness such an event," according to Alexander Petrovich Nikanorov, a researcher who briefed me at the zapovednik headquarters near Petropavlovsk. "Our lives are very short, and yet we witnessed it."

Geologists have good reason to feel that their lives, relative to the phenomena they study, are short. Rock usually moves slowly through time. But of course it's true for the rest of us also: Life is short, the world is big, and we're lucky to witness as much as we can. Whether that means we should all climb aboard the helicopter is another question, which I can't answer, not even to my own satisfaction. What I can tell you (and what Michael Melford's photographs show you) is this: Kronotsky Zapovednik is an extraordinary place, fragile and magnificent and changeable. Maybe you can take that on faith?