By Chris Carroll

National Geographic Staff

Photograph by Peter Essick

Originally printed in the National Geographic Magazine - January, 2008

June is the wet season in Ghana, but here in Accra, the capital, the morning rain has ceased. As the sun heats the humid air, pillars of black smoke begin to rise above the vast Agbogbloshie Market. I follow one plume toward its source, past lettuce and plantain vendors, past stalls of used tires, and through a clanging scrap market where hunched men bash on old alternators and engine blocks. Soon the muddy track is flanked by piles of old TVs, gutted computer cases, and smashed monitors heaped ten feet (three meters) high. Beyond lies a field of fine ash speckled with glints of amber and green—the sharp broken bits of circuit boards. I can see now that the smoke issues not from one fire, but from many small blazes. Dozens of indistinct figures move among the acrid haze, some stirring flames with sticks, others carrying armfuls of brightly colored computer wire. Most are children.

Choking, I pull my shirt over my nose and approach a boy of about 15, his thin frame wreathed in smoke. Karim says he has been tending such fires for two years. He pokes at one meditatively, and then his top half disappears as he bends into the billowing soot. He hoists a tangle of copper wire off the old tire he's using for fuel and douses the hissing mass in a puddle. With the flame retardant insulation burned away—a process that has released a bouquet of carcinogens and other toxics—the wire may fetch a dollar from a scrap-metal buyer.

Another day in the market, on a similar ash heap above an inlet that flushes to the Atlantic after a downpour, Israel Mensah, an incongruously stylish young man of about 20, adjusts his designer glasses and explains how he makes his living. Each day scrap sellers bring loads of old electronics—from where he doesn't know. Mensah and his partners—friends and family, including two shoeless boys raptly listening to us talk—buy a few computers or TVs. They break copper yokes off picture tubes, littering the ground with shards containing lead, a neurotoxin, and cadmium, a carcinogen that damages lungs and kidneys. They strip resalable parts such as drives and memory chips. Then they rip out wiring and burn the plastic. He sells copper stripped from one scrap load to buy another. The key to making money is speed, not safety. "The gas goes to your nose and you feel something in your head," Mensah says, knocking his fist against the back of his skull for effect. "Then you get sick in your head and your chest." Nearby, hulls of broken monitors float in the lagoon. Tomorrow the rain will wash them into the ocean.

People have always been proficient at making trash. Future archaeologists will note that at the tail end of the 20th century, a new, noxious kind of clutter exploded across the landscape: the digital detritus that has come to be called e-waste.

More than 40 years ago, Gordon Moore, co-founder of the computer-chip maker Intel, observed that computer processing power roughly doubles every two years. An unstated corollary to "Moore's law" is that at any given time, all the machines considered state-of-the-art are simultaneously on the verge of obsolescence. At this very moment, heavily caffeinated software engineers are designing programs that will overtax and befuddle your new turbo-powered PC when you try running them a few years from now. The memory and graphics requirements of Microsoft's recent Vista operating system, for instance, spell doom for aging machines that were still able to squeak by a year ago. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, an estimated 30 to 40 million PCs will be ready for "end-of-life management" in each of the next few years.

Computers are hardly the only electronic hardware hounded by obsolescence. A switchover to digital high-definition television broadcasts is scheduled to be complete by 2009, rendering inoperable TVs that function perfectly today but receive only an analog signal. As viewers prepare for the switch, about 25 million TVs are taken out of service yearly. In the fashion-conscious mobile market, 98 million U.S. cell phones took their last call in 2005. All told, the EPA estimates that in the U.S. that year, between 1.5 and 1.9 million tons of computers, TVs, VCRs, monitors, cell phones, and other equipment were discarded. If all sources of electronic waste are tallied, it could total 50 million tons a year worldwide, according to the UN Environment Programme.

So what happens to all this junk?

In the United States, it is estimated that more than 70 percent of discarded computers and monitors, and well over 80 percent of TVs, eventually end up in landfills, despite a growing number of state laws that prohibit dumping of e-waste, which may leak lead, mercury, arsenic, cadmium, beryllium, and other toxics into the ground. Meanwhile, a staggering volume of unused electronic gear sits in storage—about 180 million TVs, desktop PCs, and other components as of 2005, according to the EPA. Even if this obsolete equipment remains in attics and basements indefinitely, never reaching a landfill, this solution has its own, indirect impact on the environment. In addition to toxics, e-waste contains goodly amounts of silver, gold, and other valuable metals that are highly efficient conductors of electricity. In theory, recycling gold from old computer motherboards is far more efficient and less environmentally destructive than ripping it from the earth, often by surface-mining that imperils pristine rain forests.

Currently, less than 20 percent of e-waste entering the solid waste stream is channeled through companies that advertise themselves as recyclers, though the number is likely to rise as states like California crack down on landfill dumping. Yet recycling, under the current system, is less benign than it sounds. Dropping your old electronic gear off with a recycling company or at a municipal collection point does not guarantee that it will be safely disposed of. While some recyclers process the material with an eye toward minimizing pollution and health risks, many more sell it to brokers who ship it to the developing world, where environmental enforcement is weak. For people in countries on the front end of this arrangement, it's a handy out-of-sight, out-of-mind solution.

Many governments, conscious that electronic waste wrongly handled damages the environment and human health, have tried to weave an international regulatory net. The 1989 Basel Convention, a 170-nation accord, requires that developed nations notify developing nations of incoming hazardous waste shipments. Environmental groups and many undeveloped nations called the terms too weak, and in 1995 protests led to an amendment known as the Basel Ban, which forbids hazardous waste shipments to poor countries. Though the ban has yet to take effect, the European Union has written the requirements into its laws.

The EU also requires manufacturers to shoulder the burden of safe disposal. Recently a new EU directive encourages "green design" of electronics, setting limits for allowable levels of lead, mercury, fire retardants, and other substances. Another directive requires manufacturers to set up infrastructure to collect e-waste and ensure responsible recycling—a strategy called take-back. In spite of these safeguards, untold tons of e-waste still slip out of European ports, on their way to the developing world.

In the United States, electronic waste has been less of a legislative priority. One of only three countries to sign but not ratify the Basel Convention (the other two are Haiti and Afghanistan), it does not require green design or take-back programs of manufacturers, though a few states have stepped in with their own laws. The U.S. approach, says Matthew Hale, EPA solid waste program director, is instead to encourage responsible recycling by working with industry—for instance, with a ratings system that rewards environmentally sound products with a seal of approval. "We're definitely trying to channel market forces, and look for cooperative approaches and consensus standards," Hale says.

The result of the federal hands-off policy is that the greater part of e-waste sent to domestic recyclers is shunted overseas.

"We in the developed world get the benefit from these devices," says Jim Puckett, head of Basel Action Network, or BAN, a group that opposes hazardous waste shipments to developing nations. "But when our equipment becomes unusable, we externalize the real environmental costs and liabilities to the developing world."

Asia is the center of much of the world's high-tech manufacturing, and it is here the devices often return when they die. China in particular has long been the world's electronics graveyard. With explosive growth in its manufacturing sector fueling demand, China's ports have become conduits for recyclable scrap of every sort: steel, aluminum, plastic, even paper. By the mid-1980s, electronic waste began freely pouring into China as well, carrying the lucrative promise of the precious metals embedded in circuit boards.

Vandell Norwood, owner of Corona Visions, a recycling company in San Antonio, Texas, remembers when foreign scrap brokers began trolling for electronics to ship to China. Today he opposes the practice, but then it struck him and many other recyclers as a win-win situation. "They said this stuff was all going to get recycled and put back into use," Norwood remembers brokers assuring him. "It seemed environmentally responsible. And it was profitable, because I was getting paid to have it taken off my hands." Huge volumes of scrap electronics were shipped out, and the profits rolled in.

Any illusion of responsibility was shattered in 2002, the year Puckett's group, BAN, released a documentary film that showed the reality of e-waste recycling in China. Exporting Harm focused on the town of Guiyu in Guangdong Province, adjacent to Hong Kong. Guiyu had become the dumping ground for massive quantities of electronic junk. BAN documented thousands of people—entire families, from young to old—engaged in dangerous practices like burning computer wire to expose copper, melting circuit boards in pots to extract lead and other metals, or dousing the boards in powerful acid to remove gold.

China had specifically prohibited the import of electronic waste in 2000, but that had not stopped the trade. After the worldwide publicity BAN's film generated, however, the government lengthened the list of forbidden e-wastes and began pushing local governments to enforce the ban in earnest.

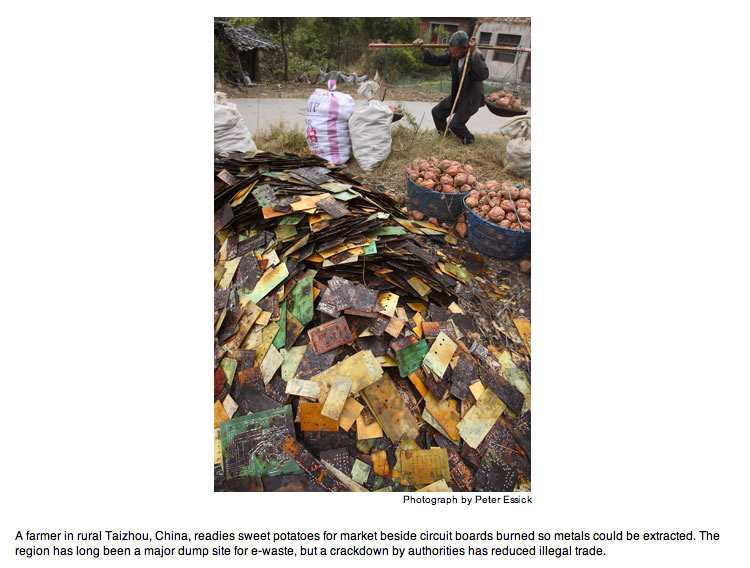

On a recent trip to Taizhou, a city in Zhejiang Province south of Shanghai that was another center of e-waste processing, I saw evidence of both the crackdown and its limits. Until a few years ago, the hill country outside Taizhou was the center of a huge but informal electronics disassembly industry that rivaled Guiyu's. But these days, customs officials at the nearby Haimen and Ningbo ports—clearinghouses for massive volumes of metal scrap—are sniffing around incoming shipments for illegal hazardous waste.

High-tech scrap "imports here started in the 1990s and reached a peak in 2003," says a high school teacher whose students tested the environment around Taizhou for toxics from e-waste. He requested anonymity from fear of local recyclers angry about the drop in business. "It has been falling since 2005 and now is hard to find."

Today the salvagers operate in the shadows. Inside the open door of a house in a hillside village, a homeowner uses pliers to rip microchips and metal parts off a computer motherboard. A buyer will burn these pieces to recover copper. The man won't reveal his name. "This business is illegal," he admits, offering a cigarette. In the same village, several men huddle inside a shed, heating circuit boards over a flame to extract metal. Outside the door lies a pile of scorched boards. In another village a few miles away, a woman stacks up bags of circuit boards in her house. She shoos my translator and me away. Continuing through the hills, I see people tearing apart car batteries, alternators, and high-voltage cable for recycling, and others hauling aluminum scrap to an aging smelter. But I find no one else working with electronics. In Taizhou, at least, the e-waste business seems to be waning.

Yet for some people it is likely too late; a cycle of disease or disability is already in motion. In a spate of studies released last year, Chinese scientists documented the environmental plight of Guiyu, the site of the original BAN film. The air near some electronics salvage operations that remain open contains the highest amounts of dioxin measured anywhere in the world. Soils are saturated with the chemical, a probable carcinogen that may disrupt endocrine and immune function. High levels of flame retardants called PBDEs—common in electronics, and potentially damaging to fetal development even at very low levels—turned up in the blood of the electronics workers. The high school teacher in Taizhou says his students found high levels of PBDEs in plants and animals. Humans were also tested, but he was not at liberty to discuss the results.

China may someday succeed in curtailing electronic waste imports. But e-waste flows like water. Shipments that a few years ago might have gone to ports in Guangdong or Zhejiang Provinces can easily be diverted to friendlier environs in Thailand, Pakistan, or elsewhere. "It doesn't help in a global sense for one place like China, or India, to become restrictive," says David N. Pellow, an ethnic studies professor at the University of California, San Diego, who studies electronic waste from a social justice perspective. "The flow simply shifts as it takes the path of least resistance to the bottom."

It is next to impossible to gauge how much e-waste is still being smuggled into China, diverted to other parts of Asia, or—increasingly—dumped in West African countries like Ghana, Nigeria, and Ivory Coast. At ground level, however, one can pick out single threads from this global toxic tapestry and follow them back to their source.

In Accra, Mike Anane, a local environmental journalist, takes me down to the seaport. Guards block us at the gate. But some truck drivers at a nearby gas station point us toward a shipment facility just up the street, where they say computers are often unloaded.

There, in a storage yard, locals are opening a shipping container from Germany. Shoes, clothes, and handbags pour out onto the tarmac. Among the clutter: some battered Pentium 2 and 3 computers and monitors with cracked cases and missing knobs, all sitting in the rain. A man hears us asking questions. "You want computers?" he asks. "How many containers?"

Near the port I enter a garage-like building with a sign over the door: "Importers of British Used Goods." Inside: more age-encrusted PCs, TVs, and audio components. According to the manager, the owner of the facility imports a 40-foot (12 meters) container every week. Working items go up for sale. Broken ones are sold for a pittance to scrap collectors.

All around the city, the sidewalks are choked with used electronics shops. In a suburb called Darkuman, a dim stall is stacked front to back with CRT monitors. These are valueless relics in wealthy countries, particularly hard to dispose of because of their high levels of lead and other toxics. Apparently no one wants them here, either. Some are monochrome, with tiny screens. Boys will soon be smashing them up in a scrap market.

A price tag on one of the monitors bears the label of a chain of Goodwill stores headquartered in Frederick, Maryland, a 45-minute drive from my house. A lot of people donate their old computers to charity organizations, believing they're doing the right thing. I might well have done the same. I ask the proprietor of the shop where he got the monitors. He tells me his brother in Alexandria, Virginia, sent them. He sees no reason not to give me his brother's phone number.

When his brother Baah finally returns my calls, he turns out not to be some shady character trying to avoid the press, but a maintenance man in an apartment complex, working 15-hour days fixing toilets and lights. To make ends meet, he tells me, he works nights and weekends exporting used computers to Ghana through his brother. A Pentium 3 brings $150 in Accra, and he can sometimes buy the machines for less than $10 on Internet liquidation websites—he favors private ones, but the U.S. General Services Administration runs one as well. Or he buys bulk loads from charity stores. (Managers of the Goodwill store whose monitor ended up in Ghana denied selling large quantities of computers to dealers.) Whatever the source, the profit margin on a working computer is substantial.

The catch: Nothing is guaranteed to work, and companies always try to unload junk. CRT monitors, though useless, are often part of the deal. Baah has neither time nor space to unpack and test his monthly loads. "You take it over there and half of them don't work," he says disgustedly. All you can do then is sell it to scrap people, he says. "What they do with it from that point, I don't know nothing about it."

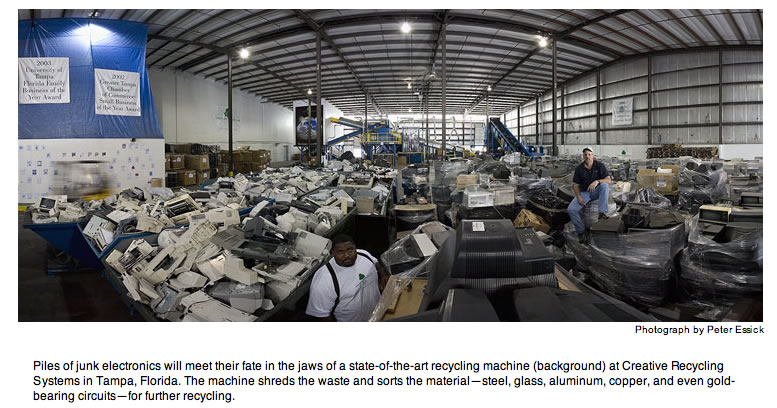

Baah's little exporting business is just one trickle in the cataract of e-waste flowing out of the U.S. and the rest of the developed world. In the long run, the only way to prevent it from flooding Accra, Taizhou, or a hundred other places is to carve a new, more responsible direction for it to flow in. A Tampa, Florida, company called Creative Recycling Systems has already begun.

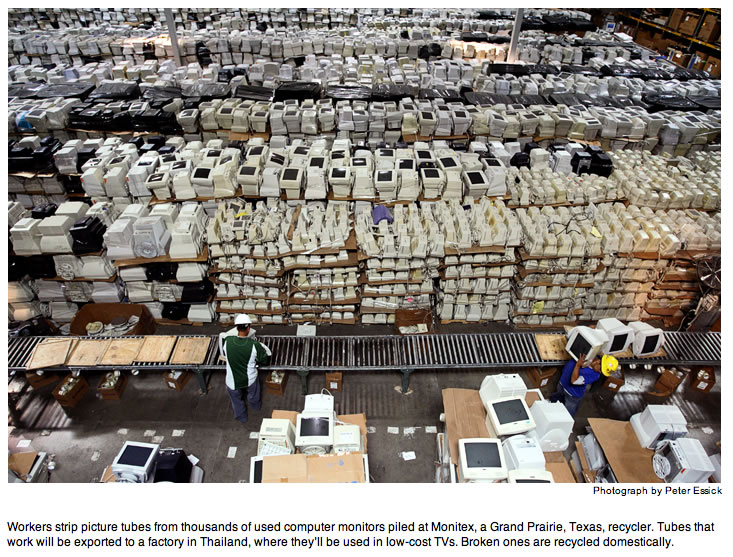

The key to the company's business model rumbles away at one end of a warehouse—a building-size machine operating not unlike an assembly line in reverse. "David" was what company president Jon Yob called the more than three-million-dollar investment in machines and processes when they were installed in 2006; Goliath is the towering stockpile of U.S. e-scrap. Today the machine's steel teeth are chomping up audio and video components. Vacuum pressure and filters capture dust from the process. "The air that comes out is cleaner than the ambient air in the building," vice president Joe Yob (Jon's brother) bellows over the roar.

A conveyor belt transports material from the shredder through a series of sorting stations: vibrating screens of varying finenesses, magnets, a device to extract leaded glass, and an eddy current separator—akin to a reverse magnet, Yob says—that propels nonferrous metals like copper and aluminum into a bin, along with precious metals like gold, silver, and palladium. The most valuable product, shredded circuit boards, is shipped to a state-of-the-art smelter in Belgium specializing in precious-metals recycling. According to Yob, a four-foot-square (1.2-meter-square) box of the stuff can be worth as much as $10,000.

In Europe, where the recycling infrastructure is more developed, plant-size recycling machines like David are fairly common. So far, only three other American companies have such equipment. David can handle some 150 million pounds (68 million kilograms) of electronics a year; it wouldn't take many more machines like it to process the entire country's output of high-tech trash. But under current policies, pound for pound it is still more profitable to ship waste abroad than to process it safely at home. "We can?t compete economically with people who do it wrong, who ship it overseas," Joe Yob says. Creative Recycling?s investment in David thus represents a gamble—one that could pay off if the EPA institutes a certification process for recyclers that would define minimum standards for the industry. Companies that rely mainly on export would have difficulty meeting such standards. The EPA is exploring certification options.

Ultimately, shipping e-waste overseas may be no bargain even for the developed world. In 2006, Jeffrey Weidenhamer, a chemist at Ashland University in Ohio, bought some cheap, Chinese-made jewelry at a local dollar store for his class to analyze. That the jewelry contained high amounts of lead was distressing, but hardly a surprise; Chinese-made leaded jewelry is all too commonly marketed in the U.S. More revealing were the amounts of copper and tin alloyed with the lead. As Weidenhamer and his colleague Michael Clement argued in a scientific paper published this past July, the proportions of these metals in some samples suggest their source was leaded solder used in the manufacture of electronic circuit boards.

"The U.S. right now is shipping large quantities of leaded materials to China, and China is the world's major manufacturing center," Weidenhamer says. "It's not all that surprising things are coming full circle and now we're getting contaminated products back." In a global economy, out of sight will not stay out of mind for long.