By John G. Mitchell

Photograph by Michael Melford

Originally printed in the National Geographic Magazine - October, 2006

By John G. Mitchell

Photograph by Michael Melford

Originally printed in the National Geographic Magazine - October, 2006

At a period in our history notable for perishable institutions, it's reassuring to know that our national parks, after all these years, remain the best idea America ever had. A British diplomat, James Bryce, rendered that judgment in 1912 when the United States could boast but a handful of parks and a new federal agency designed to look after them wouldn't be established for another four years. How time flies. A decade from now, take away a couple of months, we'll be breaking out the bubbly to celebrate the centennial of the National Park Service. That's if, the way things have been going lately, there'll be enough high standards left untrampled to justify the toast.

The Park Service and the system it oversees have come a long way since 1916: From 14 parks, 21 monuments, and one reservation embracing six million acres to 390 areas covering 84 million acres (34 million hectares) in 49 states, the District of Columbia, and islands in the Pacific and Caribbean; from a handful of rangers to a roster of 20,000 full-time employees; from 350,000 visits a year to nearly 300 million.

And I guess I could say I've come a long way too in half a century or more as a sometime visitor or critical observer of the national parks. The memory bank is filled with the sights and sounds and scents of such crown jewels as Yosemite, Everglades, Acadia, Olympic. Curiously, however, there are memories, equally cherished, of unprotected places not yet parkland when I saw them the first time around. Mineral King, for example, that remote valley in the subalpine shadow of the High Sierra's Great Western Divide, mist rising at dawn to reveal a herd of mule deer grazing 20 yards (18 meters) off the starboard side of my sleeping bag. The Disney people had wanted to build a ski resort there. But they couldn't, once the valley became a part of Sequoia National Park.

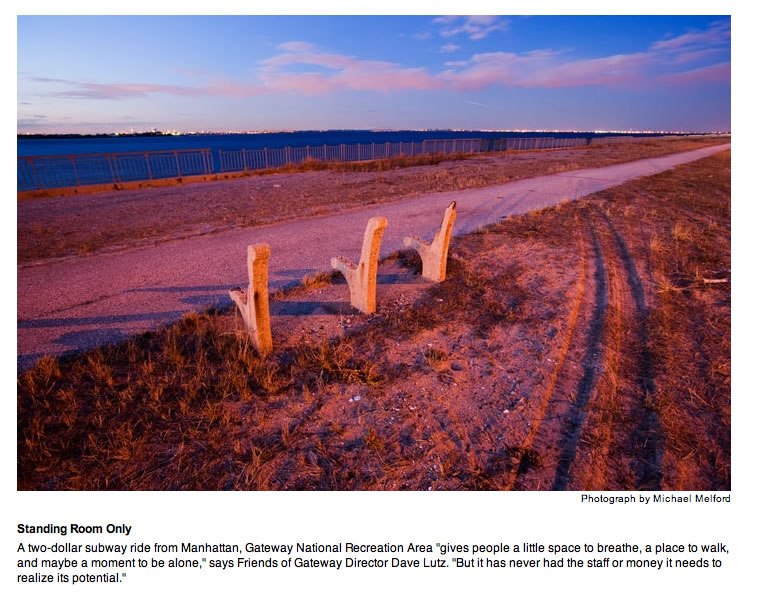

I think of Battery Weed, a skeletal 19th-century fort commanding the Narrows of New York Harbor. From the top of a bluff just minutes from my house, I regarded the neglected granite fortress with sadness, for its eventual collapse seemed inevitable. I was wrong. By and by, Battery Weed would be captured by the Park Service and tidied up as a showcase feature of Gateway National Recreation Area. Rummaging around in even older memories, I see surf pounding the white sands of Nauset Beach (now Cape Cod National Seashore in Massachusetts), wind rippling a sea of wild switchgrass in the Flint Hills of eastern Kansas (Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve), sunlight dancing across a flow of ancient lava near Grants, New Mexico (El Malpais National Monument).

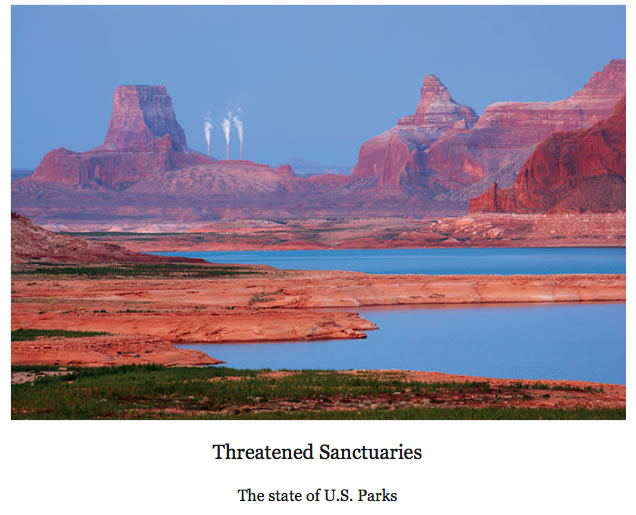

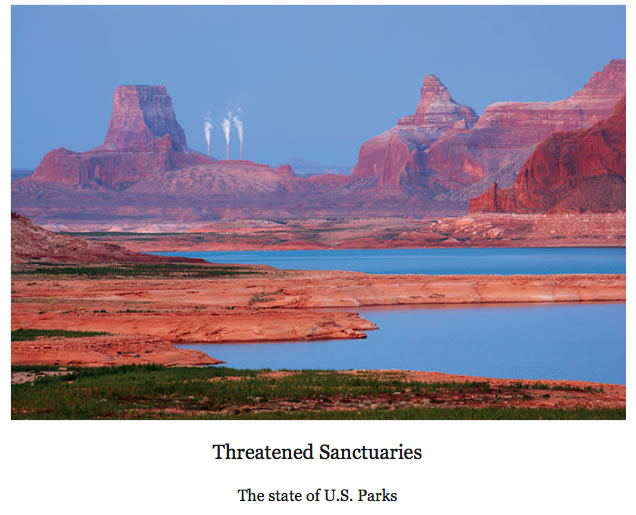

Yet for all the bright memories, there's reason to fear that America's national parks may now be facing their most daunting test. The present danger goes beyond the usual alarm that the Park Service is strapped for adequate funds to maintain the parks and therefore overwhelmed by visitors who are "loving the parks to death." That of course is a huge problem, but not a new one. Budget shortfalls have harried the Park Service and the system for many decades and under many administrations. Yet the most unsettling danger over the past five years—at least until Dirk Kempthorne replaced Gale Norton as Secretary of the Interior last May and Fran Mainella announced her intent to resign as director of the Park Service—has been an atmosphere of veiled hostility created by political appointees at the highest levels of both agencies. That atmosphere not only rattled the morale of many career professionals in the field but also assaulted the legal and regulatory fabric that has effectively held the National Park System together for 90 years.

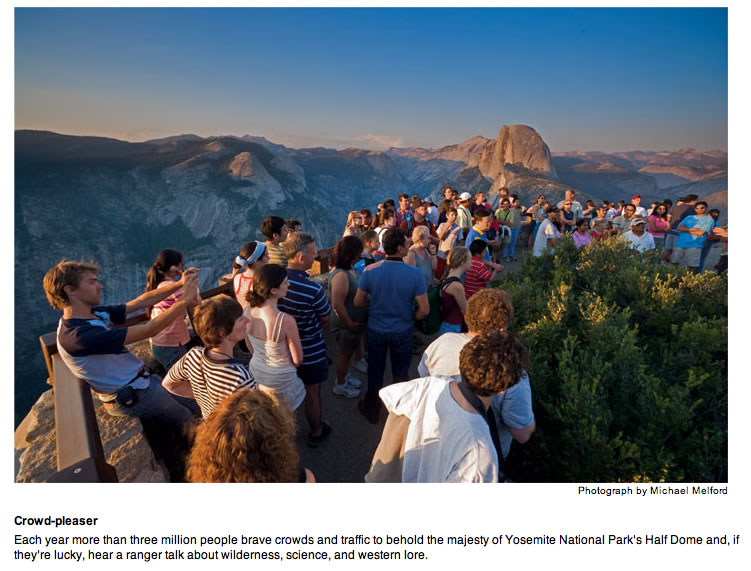

In fits and starts over those same five years, I've been taking the pulse of the Park Service and the system, talking with regional directors, park superintendents, interpretive and law enforcement rangers, and public affairs specialists. Some have retired from the agency since we spoke, a few taking early retirement rather than toeing the party line and biting their tongues behind a fixed smile. The relatively new Coalition of National Park Service Retirees now counts among its more than 500 members 5 former directors or deputy directors, 26 regional directors or deputies, and 130 park superintendents and assistant superintendents. Many of these former top professionals put in for retirement since 2001. "We're losing some of our best people," a ranger said to me last year at Yosemite Valley. "Where is it going to end?"

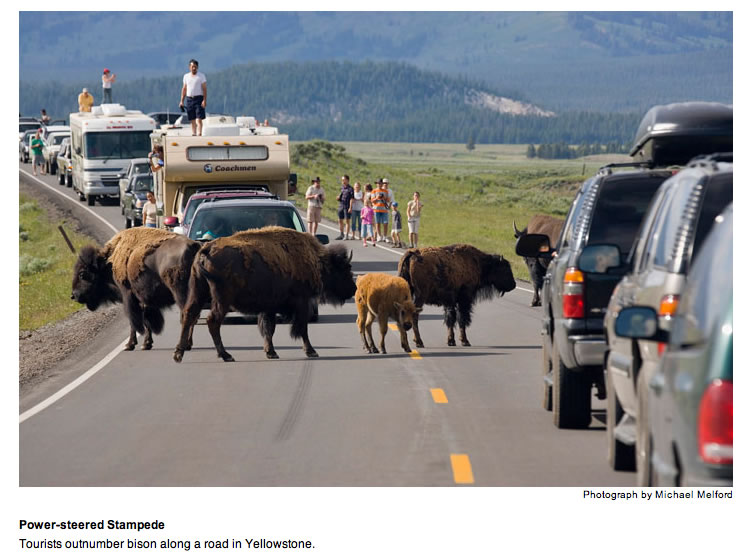

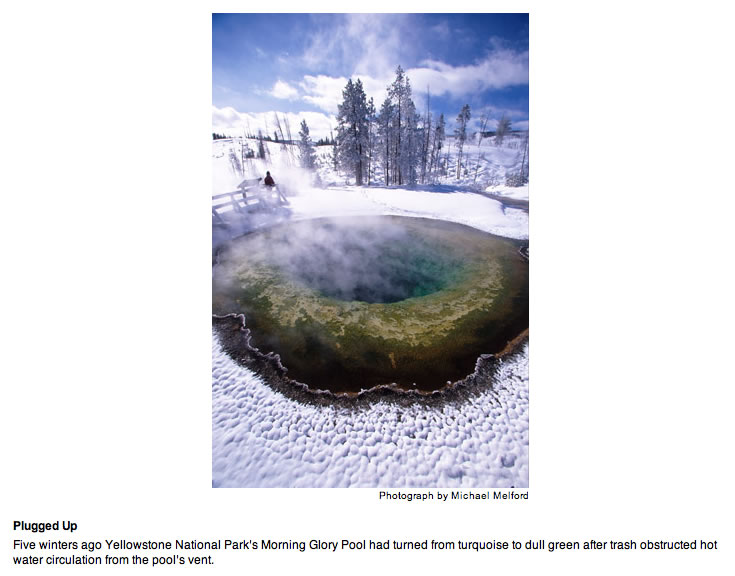

Visitors to the parks are unaware of these tensions. For all the erosion of agency morale, the wear and tear, the backlog of uncompleted maintenance and repair projects, the widespread reductions of interpretive programs, national parks can still deliver a memorable experience. With patience and binoculars, one may now observe wolves as well as bison at Yellowstone National Park. Given gravity and sufficient precipitation, Yosemite's Bridalveil Fall will continue to ensorcell viewers for years to come. But what of some of the other values of the larger Yellowstone and Yosemite? Unspoiled habitat. Wilderness. Solitude. High country silence. Is it time to begin to wonder if we are about to lose the best of these, too?

Most historians trace the origin of America's "best idea" to the frontier artist George Catlin who, in 1832, after a tour sketching the tribes of the Great Plains, expressed hope that the government might set aside a vast section of the West for "a nation's Park, containing man and beast, in all the wild and freshness of their nature's beauty." But it would be 32 years before the U.S. made its first tentative move in that direction, transferring a federally owned Yosemite Valley and a nearby grove of sequoias to the State of California to hold in trust for the entire nation as a place for public use and recreation. Eight years later Congress established Yellowstone as our first official national park, and Yosemite went federal as a national park in 1890.

In subsequent years, other congressional mandates authorized additional parks, battlefield sites, and memorials, and the Antiquities Act of 1906 enabled a President to proclaim a national monument on federal land without congressional consent. By 1916 the U.S. Department of the Interior had jurisdiction over 35 parks and monuments, and in August of that year President Woodrow Wilson signed an act establishing within Interior a National Park Service to manage and protect those areas and others that might be authorized in the future (such as the more than 50 monuments, military sites, and other areas it took over from the Forest Service and the War Department in the 1930s).

If any decade after that was to demonstrate how far the National Park System could move beyond its traditional image, rooted in the scenic values of the big western parks, it was the 1960s—the years of President Lyndon Johnson, Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall, and a hard-charging Park Service director named George Hartzog. Udall and Hartzog wanted to break new ground, but first Congress would have to eschew its own tradition of creating parks on the cheap, either carved from existing federal lands or purchased with other people's money, principally that of philanthropist John D. Rockefeller and his family. Enactment of the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act, primed mostly with receipts from oil and gas leasing on the outer continental shelf, soon helped the service develop a new menu of parklands: national lakeshores, wild and scenic rivers, national trails, and, last but not least in terms of visitor use and operating expense, the urban recreation areas that would fulfill Lyndon Johnson's dream of bringing nature closer to people.

If anyone feared that the rush to establish national recreation areas in or adjacent to such metropolises as New York City and San Francisco meant the end of acquiring big scenic parks in the far country, that suspicion soon faded as President Jimmy Carter moved to secure 40 million acres (16 million hectares) of federal lands in Alaska for the National Park Service, first putting them "on hold" by invoking the Antiquities Act, and then by designating nine new parks and preserves and sizably expanding existing ones, such as Denali, with passage of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980. In the stroke of a pen, President Carter had more than doubled the acreage of the National Park System.

Noting the huge responsibility that any new unit, of whatever size or category, places on the shoulders of an overextended, underfunded Park Service, a few observers began to cast a critical eye on a growing genre of historic sites commemorating not some classic or heroic moment from America's past, as in a Civil War battlefield or presidential birthplace, but rather a salute to a place or event perceived as having limited national significance, as in the case of Steamtown National Historic Site at Scranton, Pennsylvania, established to interpret the story of steam railroads in the 20th century. The purists saw danger in these designations and warned they could lead, as one top official put it, to "a thinning of the [Park Service's] blood." A misguided handful even objected to designating sites exploring the darker, often shameful side of American history, as at Manzanar in California's Owens Valley, where thousands of innocent Japanese-American citizens were interned during World War II. But a reluctance to open all aspects of our history to a fuller interpretation soon passed away. Even the old Custer Battlefield National Monument in Montana would acquire a fresh look and a new name—Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument—to give an accurate account of the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho side of the story.

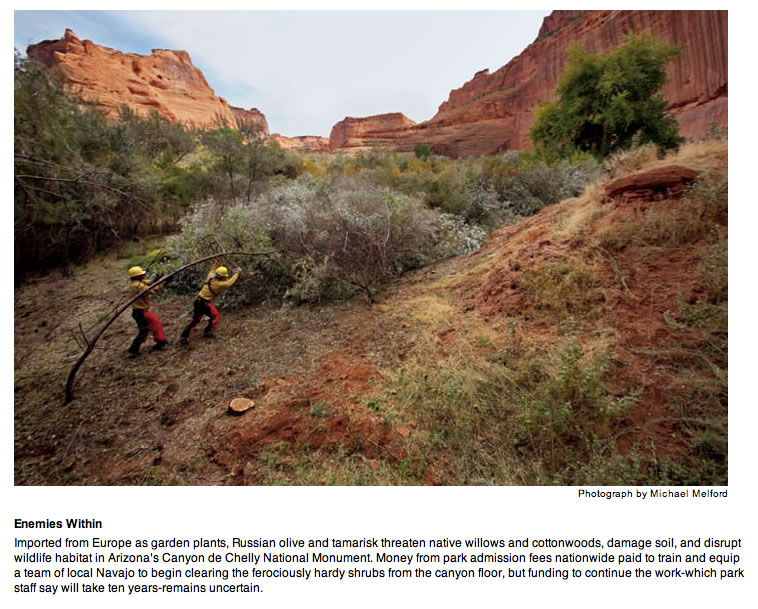

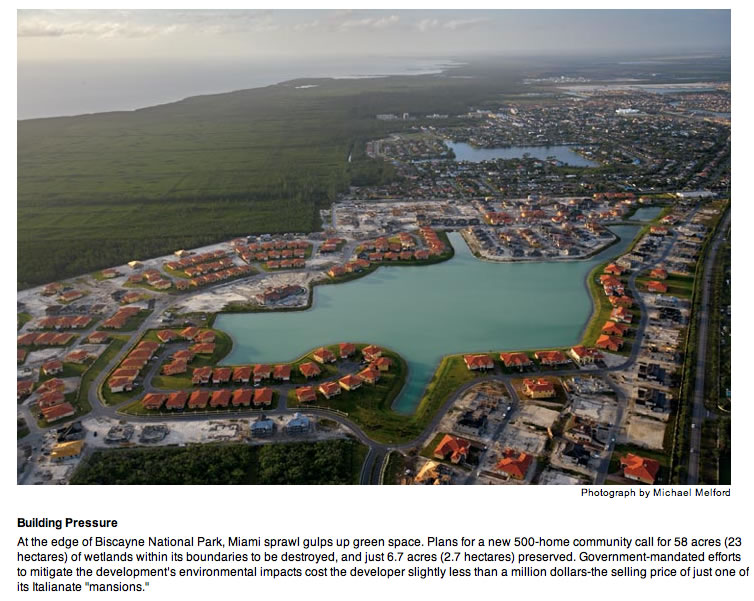

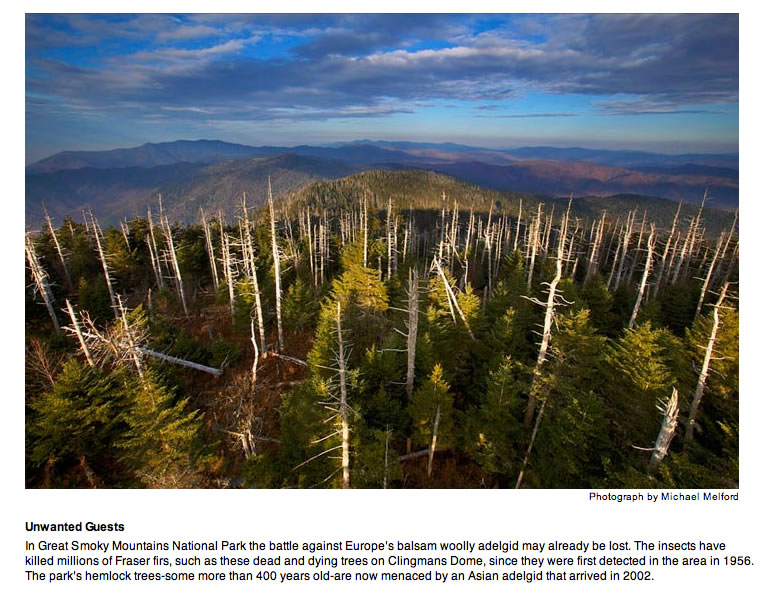

Nineteen-ninety-three was the last time the editors of this magazine posted me across the country to assess the state of the national parks. I didn't hear too much grumbling then about thinned blood or revisionist history. But what I did hear from rank and file in the Park Service was a huge concern that the nation's treasures were threatened by industrial and automotive air pollution, invasive species, and a variety of human encroachments nibbling at the edges of hallowed ground. The most persistent complaint, however, was a perception that the Park Service had lost its ability to protect natural and cultural resources, largely because its rangers had morphed into traffic cops to accommodate growing throngs of park-loving visitors. All these problems and many more continue to plague the service and the system—notably the contentious issue of protection versus use.

The legislation establishing the National Park Service 90 years ago, the so-called Organic Act, stipulated that the purpose of parks and monuments—indeed, the agency's core mission—"is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations." But over the years there has been much disagreement over which comes first, the resource or the visitor. Not only that, but at what point does resource impairment begin to result from a good time being had by all?

Five years ago the National Park System Advisory Board, a distinguished panel appointed by the Secretary of the Interior, issued a report describing how the Park Service, early on, had discovered that the best way to win public support for the parks was to make sure the visitors derived pleasure from them. However, managing for people (as in the suppression of forest fires) often resulted in bad news for resources (a buildup of forest debris fueling deadlier fires). "It is time," the board declared in Rethinking the National Parks for the 21st Century, "to re-examine the 'enjoyment equals support' equation and to encourage public support of resource protection at a higher level of understanding. In giving priority to visitor services, the Park Service has paid less attention to the resources it is obliged to protect for future generations."

For the most part career professionals in the Park Service found the report much to their liking. But that was not the reaction among political appointees in the Bush Administration. Though Park Service Director Fran Mainella initially supported the report, it later became evident that it was not her agenda, and before long the Department of the Interior, under Secretary Norton, was suggesting the opposite of what the board had concluded: Preservation was trumping recreation; the Clinton Administration had taken the fun out of national parks. Now the stage was set for a clash of values.

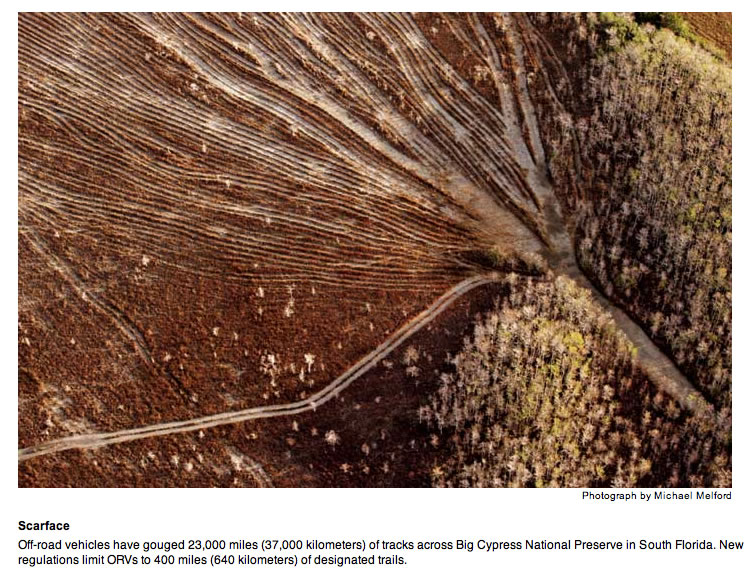

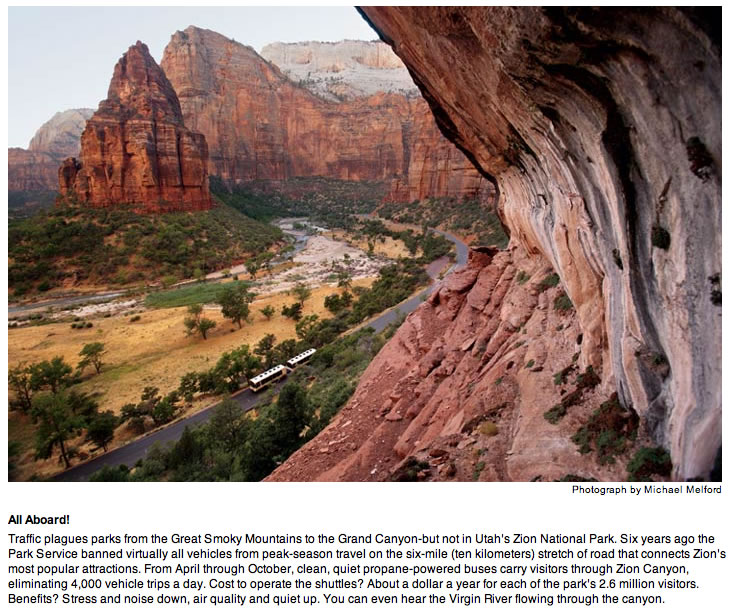

In the summer of 2005, Interior was obliged to make public—after it was leaked—a 195-page revision of the Park Service's basic policy document, essentially altering the way parks were to be managed in the future. The rewrite was the work of Paul Hoffman, at the time Interior's deputy assistant secretary for fish, wildlife, and parks, a former executive director of the Cody, Wyoming, chamber of commerce, and congressional aide to Dick Cheney in the 1980s. Among Hoffman's most radical policy tweaks were calls to open to snowmobiles all national park roads used by motor vehicles in other seasons, as well as a relaxation of restrictions on personal watercraft at some national seashores and lakeshores and on noisy tourist flights over such parks as Great Smoky Mountains and Glacier.

Charging that these revisions would override 90 years of established laws and court rulings, more than a few park superintendents expressed alarm. "I hope the public understands that this is a threat to their heritage," J. T. Reynolds, superintendent at Death Valley National Park, told the Los Angeles Times. Bill Wade, for many years superintendent of Shenandoah National Park but now retired and speaking as chairman of the Coalition of National Park Service Retirees, called the Hoffman document an "astonishing attempt to hijack" the nation's parks "and convert them into vastly diminished areas where almost anything goes." And it came as no surprise that the rewrite paid scant attention to the importance of promoting science-based programs in the national parks.

Oceanographer Sylvia Earle, a National Geographic Society explorer-in-residence, and a panel of her peers, including Harvard biologist E. O. Wilson, had already filed a report urging the Park Service to "continue to develop a robust, professional scientific natural resource management program." The group insisted that "it is absolutely essential for scientific knowledge to form the foundation for any meaningful effort to preserve ecological resources in the National Park System." Approved by the National Park System Advisory Board, the Earle report was forwarded to Park Service Director Fran Mainella. But the report was never printed and distributed and did not show up on the Park Service website for seven months.

Michael Soukup is the agency's associate director for natural resource stewardship and science, and he is not inclined to bite his tongue when asked if scientific expression was being sidelined in the National Park System. Until recent changes at Interior, he told me, "Science was not only being sidelined. It was under siege."

After a storm of protest within the Park Service and an outcry in the press, Mainella's office last fall issued for public comment a muted version of the Hoffman policy rewrite. ("Hoffman Lite," some critics called it.) Some of the original policy changes favoring motorized recreation were toned down or eliminated altogether, but still intact was the challenge to the primacy of protection over use. Senate and House committees charged with oversight of the National Park System conducted hearings. Possibly the most persistent criticism heard was that a rewrite of a bad policy revision was without merit or justification. "To polish the apple when it is rotten at its core is a waste of time," said Bill Wade, the retired Shenandoah superintendent, referring to the attempt to lighten up Hoffman Heavy. Nonetheless, the Senate Subcommittee on National Parks heard one William Horn testify that Clinton-era policy was "overtly hostile" to traditional use. Visitors, he said, shouldn't be kept "on the other side of the . . . fence." Horn identified himself as a former Interior assistant secretary for fish, wildlife, and parks in the Reagan Administration but neglected to mention his current position as an attorney for the International Snowmobile Manufacturers Association.

Rebutting Horn's argument was Denis Galvin, a retired deputy director of the Park Service who served under three Presidents and who did identify his current affiliation as a trustee of the National Parks Conservation Association, a nonprofit advocacy organization. Galvin wondered how people could feel fenced out when tens of millions of them visit national parks every year and almost invariably respond in surveys that they thoroughly enjoy the experience. "The national parks do not have to sustain all recreation," he said. "That is why we have various other federal, state, local, and private recreation providers . . . to provide for those types of recreation that generally do not belong in the national parks."

Speaking at the House Resources Committee hearing a few months later, Stephen Martin, deputy director of the National Park Service, questioned, in effect, what all the fuss was about. Denying there had been any attempt to manipulate the agency's core mission, Martin testified that the new draft policies "underscore that when there is a conflict between use and conservation, the protection of the resource will be predominant." That interpretation, in fact, was strongly endorsed with the release in June of yet another draft, which rejected earlier revisions, conceded virtually every point of contention, and returned to the original policies the revisionists had sought to undercut.

The House Resources Committee, presided over by Richard Pombo (R-Calif.), broke briefly into the news earlier this year when Pombo's staff drafted a budget reconciliation proposal to sell off 15 national park areas for commercial or energy development and slather the remaining units with paid advertisements on park shuttle buses. Among the places on the hit list, each selected for its failure to attract more than 10,000 visitors a year, were seven remote and wild areas in Alaska totaling some 19 million acres (8 million hectares). Pombo's staffers also proposed turning the wooded 88-acre (36 hectares) Theodore Roosevelt Island in the Potomac River—the capital city's fitting memorial to the President who put an uppercase C on the word Conservation—into a conclave of offices and condominiums.

These proposals did not rest well with members of Congress. Pombo's staff rushed to deflate their significance, describing them as a "theoretical exercise" and a "joke." The boss didn't really want to sell off national parks, it was said. Some budget-watchers suggested it was a ploy to demonstrate what it would take to offset the loss of anticipated federal revenue should obstructionists continue to block oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Campaigning for the presidency in 2000, George W. Bush pledged that, if elected, he would wipe out the huge 4.9-billion-dollar backlog in deferred maintenance of the national parks' crumbling infrastructure. Given the fallout from 9/11, among other things, it was not to be. This year, in its budget request for fiscal 2007, the White House proposed cutting the Park Service's budget by 5 percent, or a hundred million dollars. Most of those missing dollars would come off the top of the service's construction and major maintenance funds, prompting the New York Times to suggest in a lead editorial that such deliberate cuts "could create the necessary cover for opening the parks to more commercial activity."

A concern that parks might be turned into profit centers developed several years ago when the Interior Department and parks director Mainella began studying the possibility of outsourcing certain services, such as landscaping, to competitive contractors. At the time, the initiative's targets were limited to a handful of jobs. Last year it appeared that the outsourcers were considering something broader when Mainella was directed to issue a memo announcing that entire programs at three parks—Boston National Historical Park, Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, and San Juan National Historic Site in Puerto Rico—would be studied for possible handoffs to the lowest bidders. Mainella later rescinded her memo. But the specter of commerce-in-the-parks would not soon go away. Last fall the director's office proposed that superintendents be permitted to solicit corporate donations and then reward donors by displaying their brand names on prominent park facilities. In the face of strong public protests, the director's office reversed itself once again and issued new guidelines applauded even by some park advocacy organizations.

"Philanthropy has long been a tradition in the National Park System," John Piltzecker, head of the service's donations and fund-raising programs, told me. He noted that "Friends" groups, cooperating associations, and the National Park Foundation already pour more than 75 million dollars into the parks annually, and he assured me that efforts will continue to keep donor recognition "low profile" and "in good taste."

Despite the institutional hiccups over the past five years, the next ten could prove a bit less bleak for the National Park Service. Two presidential elections will fall into that time frame, and the first one will usher in a new administration regardless of which party wins. In my sorties afield, I discovered that some of the service's remnant best people are toughing it out under their Smokey Bear hats. "The glass is half full, not half empty," says Gary Davis, chief scientist for ocean programs in the National Park System. At Pacific West Regional headquarters in Oakland, California, Jon Jarvis, the director, pegs his own hopefulness to the Organic Act, which obliges the Park Service to hold the parks in trust for "future generations." That's the law, says Jarvis, "and unless it's repealed, you can't get any more optimistic than that."

But what will those future generations be like? Certainly not like mine. Diversity is leaving its mark on the demographics of the United States. Euro-Americans, as non-Hispanic whites are often called nowadays, already are a minority in some regions of the country. "We've been talking all these years to the people who come to the parks," says Howard Levitt, chief of interpretation at Golden Gate National Recreation Area in San Francisco. "Now we must learn how to speak with the people who haven't been coming."

Levitt's boss, Golden Gate Superintendent Brian O'Neill, told me 13 years ago that his agency's fundamental challenge would be to make every individual in an increasingly diverse population "a real stakeholder, emotionally and intellectually, in the National Park System." Was that still the challenge, I asked O'Neill when I saw him recently. "You bet it is," he said. "Now more than ever."