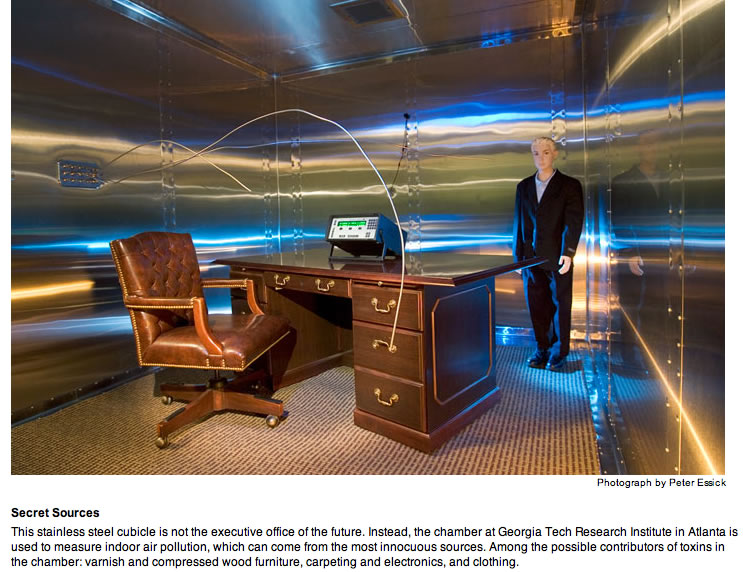

Pollution Inside Us

Modern chemistry keeps insects from ravaging crops, liftsstains from carpets, and saves lives. But the ubiquity of chemicals is taking atoll.

By David Ewing Duncan

Originally printed in the National Geographic Magazine - October, 2006

My journalist-as-guinea-pig experiment is taking adisturbing turn. A Swedish chemist is on the phone, talking about flameretardants, chemicals added for safety to just about any product that can burn.Found in mattresses, carpets, the plastic casing of televisions, electroniccircuit boards, and automobiles, flame retardants save hundreds of lives a yearin the United States alone. These, however, are where they should not be:inside my body.

Āke Bergman of Stockholm University tells me he has receivedthe results of a chemical analysis of my blood, which measured levels offlame-retarding compounds called polybrominated diphenyl ethers. In mice andrats, high doses of PBDEs interfere with thyroid function, cause reproductiveand neurological problems, and hamper neurological development. Little is knownabout their impact on human health.

"I hope you are not nervous, but this concentration isvery high," Bergman says with a light Swedish accent. My blood level ofone particularly toxic PBDE, found primarily in U.S.-made products, is 10 timesthe average found in a small study of U.S. residents and more than 200 timesthe average in Sweden. The news about another PBDE variant—also toxic toanimals—is nearly as bad. My levels would be high even if I were a worker in afactory making the stuff, Bergman says.

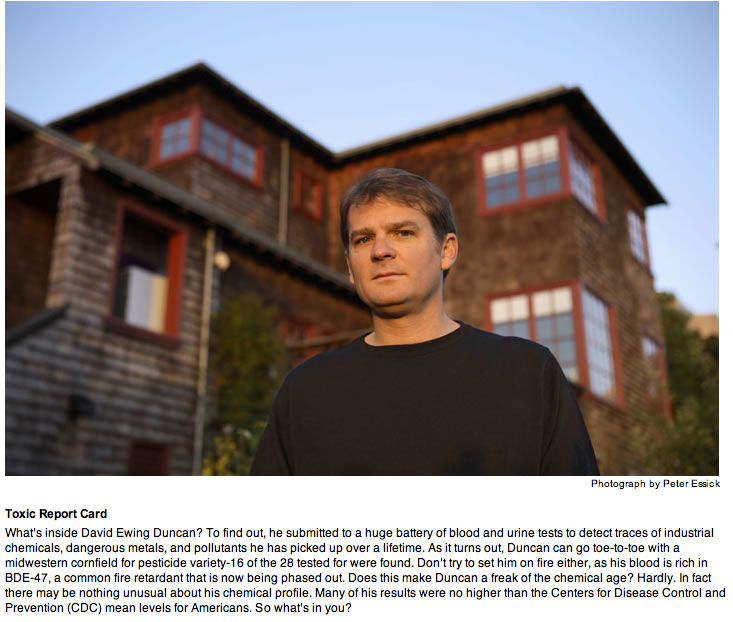

In fact I'm a writer engaged in a journey of chemicalself-discovery. Last fall I had myself tested for 320 chemicals I might havepicked up from food, drink, the air I breathe, and the products that touch myskin—my own secret stash of compounds acquired by merely living. It includesolder chemicals that I might have been exposed to decades ago, such as DDT andPCBs; pollutants like lead, mercury, and dioxins; newer pesticides and plasticingredients; and the near-miraculous compounds that lurk just beneath thesurface of modern life, making shampoos fragrant, pans nonstick, and fabricswater-resistant and fire-safe.

The tests are too expensive for most individuals—NationalGeographic paid for mine, which would normally cost around $15,000—and only afew labs have the technical expertise to detect the trace amounts involved. Iran the tests to learn what substances build up in a typical American over alifetime, and where they might come from. I was also searching for a way tothink about risks, benefits, and uncertainty—the complex trade-offs embodied inthe chemical "body burden" that swirls around inside all of us.

Now I'm learning more than I really want to know.

Bergman wants to get to the bottom of my flame-retardantmystery. Have I recently bought new furniture or rugs? No. Do I spend a lot oftime around computer monitors? No, I use a titanium laptop. Do I live near afactory making flame retardants? Nope, the closest one is over a thousand miles(1,600 kilometers) away. Then I come up with an idea.

"What about airplanes?" I ask.

"Yah," he says, "do you fly a lot?"

"I flew almost 200,000 miles (300,000 kilometers) lastyear," I say. In fact, as I spoke to Bergman, I was sitting in an airportwaiting for a flight from my hometown of San Francisco to London.

"Interesting," Bergman says, telling me that hehas long been curious about PBDE exposure inside airplanes, whose plastic andfabric interiors are drenched in flame retardants to meet safety standards setby the Federal Aviation Administration and its counterparts overseas. "Ihave been wanting to apply for a grant to test pilots and flight attendants forPBDEs," Bergman says as I hear my flight announced overhead. But for nowthe airplane connection is only a hypothesis. Where I picked up this chemicalthat I had not even heard of until a few weeks ago remains a mystery. Andthere's the bigger question: How worried should I be?

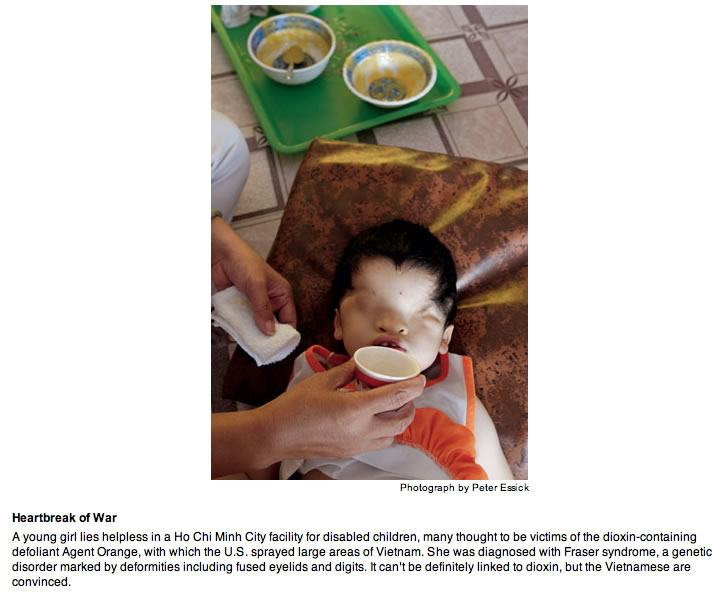

The same can be asked of other chemicals I've absorbed fromair, water, the nonstick pan I used to scramble my eggs this morning, myfaintly scented shampoo, the sleek curve of my cell phone. I'm healthy, and asfar as I know have no symptoms associated with chemical exposure. In largedoses, some of these substances, from mercury to PCBs and dioxins, the notoriouscontaminants in Agent Orange, have horrific effects. But many toxicologists—andnot just those who have ties to the chemical industry—insist that the minusculesmidgens of chemicals inside us are mostly nothing to worry about.

"In toxicology, dose is everything," says KarlRozman, a toxicologist at the University of Kansas Medical Center, "andthese doses are too low to be dangerous." One part per billion (ppb), astandard unit for measuring most chemicals inside us, is like putting half ateaspoon (two milliliters) of red dye into an Olympic-size swimming pool.What's more, some of the most feared substances, such as mercury, dissipatewithin days or weeks—or would if we weren't constantly re-exposed.

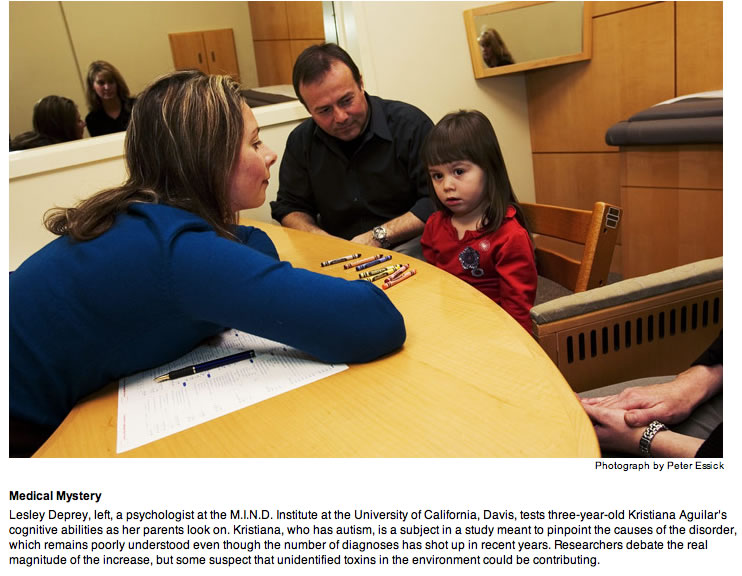

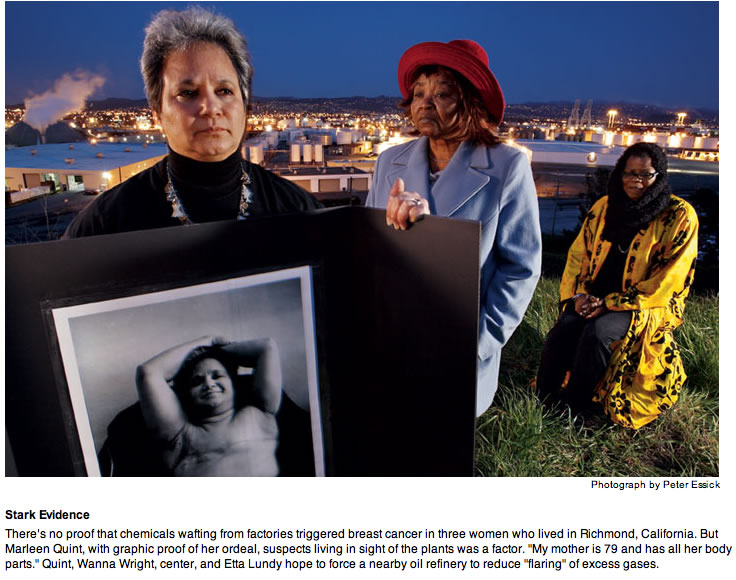

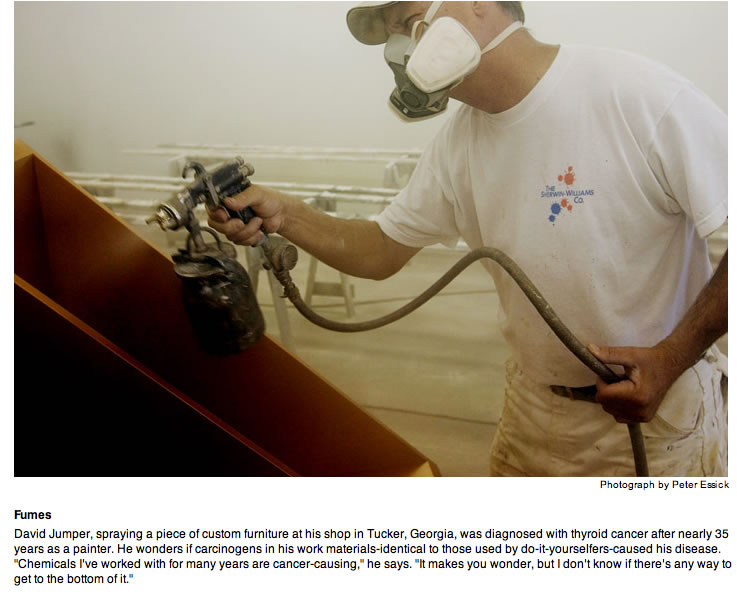

Yet even though many health statistics have been improvingover the past few decades, a few illnesses are rising mysteriously. From theearly 1980s through the late 1990s, autism increased tenfold; from the early1970s through the mid-1990s, one type of leukemia was up 62 percent, male birthdefects doubled, and childhood brain cancer was up 40 percent. Some expertssuspect a link to the man-made chemicals that pervade our food, water, and air.There's little firm evidence. But over the years, one chemical after anotherthat was thought to be harmless turned out otherwise once the facts were in.

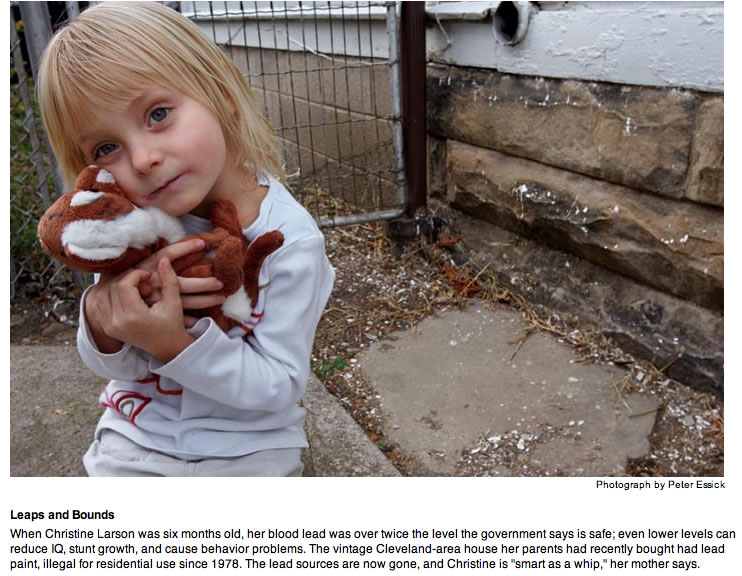

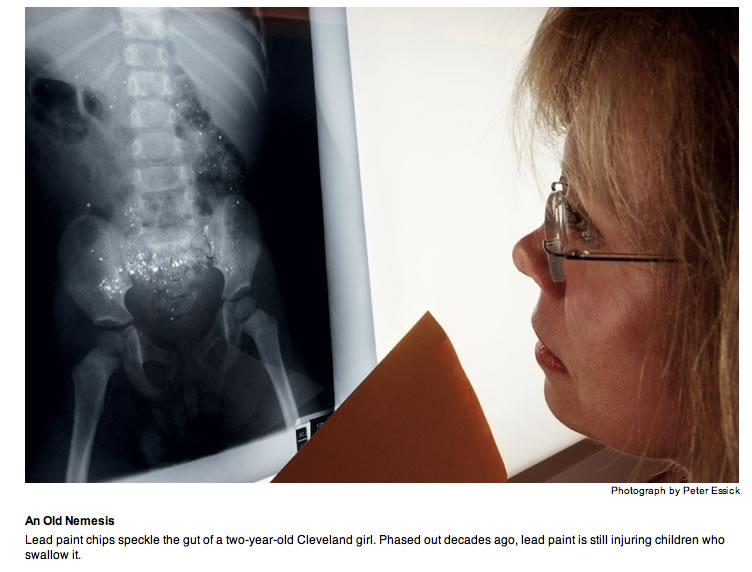

The classic example is lead. In 1971 the U.S. SurgeonGeneral declared that lead levels of 40 micrograms per deciliter of blood weresafe. It's now known that any detectable lead can cause neurological damage inchildren, shaving off IQ points. From DDT to PCBs, the chemical industry hasreleased compounds first and discovered damaging health effects later.Regulators have often allowed a standard of innocent until proven guilty inwhat Leo Trasande, a pediatrician and environmental health specialist at MountSinai Hospital in New York City, calls "an uncontrolled experiment onAmerica's children."

Each year the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)reviews an average of 1,700 new compounds that industry is seeking tointroduce. Yet the 1976 Toxic Substances Control Act requires that they betested for any ill effects before approval only if evidence of potential harmexists—which is seldom the case for new chemicals. The agency approves about 90percent of the new compounds without restrictions. Only a quarter of the 82,000chemicals in use in the U.S. have ever been tested for toxicity.

Studies by the Environmental Working Group, an environmentaladvocacy organization that helped pioneer the concept of a "bodyburden" of toxic chemicals, had found hundreds of chemical traces in thebodies of volunteers. But until recently, no one had even measured averagelevels of exposure among large numbers of Americans. No regulations requiredit, the tests are expensive, and technology sensitive enough to measure thetiniest levels didn't exist.

Last year the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention(CDC) took a step toward closing that gap when it released data on 148substances, from DDT and other pesticides to metals, PCBs, and plasticingredients, measured in the blood and urine of several thousand people. Thestudy said little about health impacts on the people tested or how they mighthave encountered the chemicals. "The good news is that we are getting realdata about exposure levels," says James Pirkle, the study's lead author."This gives us a place to start."

I began my own chemical journey on an October morning at theMount Sinai Hospital in New York City, where I gave urine and had blood drawnunder the supervision of Leo Trasande. Trasande specializes in childhoodexposures to mercury and other brain toxins. He had agreed to be one of severalexpert advisers on this project, which began as a Sinai phlebotomist extracted14 vials of blood—so much that at vial 12 I felt woozy and went into a coldsweat. At vial 13 Trasande grabbed smelling salts, which hit my nostrils like awhiff of fire and allowed me to finish.

From New York my samples were shipped to Axys AnalyticalServices on Vancouver Island in Canada, one of a handful of state-of-the-artlabs specializing in subtle chemical detection, analyzing everything from eagleeggs to human tissue for researchers and government agencies. A few weekslater, I followed my samples to Canada to see how Axys teased out the tinyloads of compounds inside me.

I watched the specimens go through multiple stages ofprocessing, which slowly separated sets of target chemicals from the thousandsof other compounds, natural and unnatural, in my blood and urine. The extractsthen went into a high-tech clean room containing mass spectrometers, sleek,freezer-size devices that work by flinging the components of a sample through avacuum, down a long tube. Along the way, a magnetic field deflects themolecules, with lighter molecules swerving the most. The exact amount ofdeflection indicates each molecule's size and identity.

A few weeks later, Axys sent me my results—a grid of numbersin parts per billion or trillion—and I set out to learn, as best I could, wherethose toxic traces came from.

Some of them date back to my time in the womb, when mymother downloaded part of her own chemical burden through the placenta and theumbilical cord. More came after I was born, in her breast milk.

Once weaned, I began collecting my own chemicals as I grewup in northeastern Kansas, a few miles outside Kansas City. There I spentcountless hot, muggy summer days playing in a dump near the Kansas River.Situated on a high limestone bluff above the fast brown water lined bycottonwoods and railroad tracks, the dump was a mother lode of old bottles,broken machines, steering wheels, and other items only boys can fullyappreciate.

This was the late 1960s, and my friends and I had no way ofknowing that this dump would later be declared an EPA superfund site, on theNational Priority List for hazardous places. It turned out that for years,companies and individuals in this corner of Johnson County had dumped thousandsof pounds of material contaminated with toxic chemicals here. "It was startedas a landfill before there were any rules and regulations on how landfills weredone," says Denise Jordan-Izaguirre, the regional representative for thefederal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. "There weremetal tailings and heavy metals dumped in there. It was unfenced, unrestricted,so kids had access to it."

Kids like me.

Now capped, sealed, and closely monitored, the dump, calledthe Doepke-Holliday Site, also happens to be half a mile upriver from a countywater intake that supplied drinking water for my family and 45,000 otherhouseholds. "From what we can gather, there were contaminants going intothe river," says Shelley Brodie, the EPA Remedial Project Manager forDoepke. In the 1960s, the county treated water drawn from the river, but notfor all contaminants. Drinking water also came from 21 wells that tapped theaquifer near Doepke.

When I was a boy, my corner of Kansas was filthy, and thedump wasn't the only source of toxins. Industry lined the river a few milesaway—factories making cars, soap, and fertilizers and other agriculturalchemicals—and a power plant belched fumes. When we drove past the plants towarddowntown Kansas City, we plunged into a noxious cloud that engulfed the carwith smoke and an awful chemical stench. Flames rose from fertilizer plantstacks, burning off mustard-yellow plumes of sodium, and animal waste pouredinto the river. In the nearby farmland, trucks and crop dusters sprayed DDT andother pesticides in great, puffy clouds that we kids sometimes rode our bikesthrough, holding our breath and feeling very brave.

Today the air is clear, and the river free of effluents—avisible testament to the success of the U.S. environmental cleanup, spurred bythe Clean Air and Clean Water Acts of the 1970s. But my Axys test results readlike a chemical diary from 40 years ago. My blood contains traces of severalchemicals now banned or restricted, including DDT (in the form of DDE, one ofits breakdown products) and other pesticides such as the termite-killerschlordane and heptachlor. The levels are about what you would expect decadesafter exposure, says Rozman, the toxicologist at the University of KansasMedical Center. My childhood playing in the dump, drinking the water, andbreathing the polluted air could also explain some of the lead and dioxins inmy blood, he says.

I went to college at a place and time that put me at theheight of exposure for another set of substances found inside me—PCBs, onceused as electrical insulators and heat-exchange fluids in transformers andother products. PCBs can lurk in the soil anywhere there's a dump or an oldfactory. But some of the largest releases took place along New York's HudsonRiver from the 1940s to the 1970s, when General Electric used PCBs at factoriesin the towns of Hudson Falls and Fort Edward. About 140 miles (225 kilometers)downstream is the city of Poughkeepsie, where I attended Vassar College in thelate 1970s.

PCBs, oily liquids or solids, can persist in the environmentfor decades. In animals, they impair liver function, raise blood lipids, andcause cancers. Some of the 209 different PCBs chemically resemble dioxins andcause other mischief in lab animals: reproductive and nervous system damage, aswell as developmental problems. By 1976, the toxicity of PCBs was unmistakable;the United States banned them, and GE stopped using them. But until then, GElegally dumped excess PCBs into the Hudson, which swept them all the waydownriver to Poughkeepsie, one of eight cities that draw their drinking waterfrom the Hudson.

In 1984, a 200-mile (300 kilometers) stretch of the Hudson,from Hudson Falls to New York City, was declared a superfund site, and plans torid the river of PCBs were set in motion. GE has spent 300 million dollars onthe cleanup so far, dredging up and disposing of PCBs in the river sedimentunder the supervision of the EPA. It is also working to stop the seepage ofPCBs into the river from the factories.

Birds and other wildlife along the Hudson are thought tohave suffered from the pollution, but its impact on humans is less definitive.One study in Hudson River communities found a 20 percent increase in the rateof hospitalization for respiratory diseases, while another, more reassuringly,found no increase in cancer deaths in the contaminated region. But among manyof the locals, the fear is palpable.

"I grew up a block from the Fort Edward plant,"says Dennis Prevost, a retired Army officer and public health advocate, whoblames PCBs for the brain cancers that killed his brother at age 46 and aneighbor in her 20s. "The PCBs have migrated under the parking lot andinto the community aquifer," which Prevost says was the source of FortEdward's drinking water until municipal water replaced wells in 1984.

Ed Fitzgerald of the State University of New York at Albany,a former staff scientist at the state department of health, is conducting themost thorough study yet of the health effects of PCBs in the area. He says hehas explained to Prevost and other residents that the risk from the wells wasprobably small because PCBs tend to settle to the bottom of an aquifer. Eatingcontaminated fish caught in the Hudson is a more likely exposure route, hesays.

I didn't eat much Hudson River fish during my college daysin the 1970s, but the drinking water in my dorm could have contained traces ofthe PCBs pouring into the river far upstream. That may be how I picked up myPCB body burden, which was about average for an American. Or maybe not."PCBs are everywhere," says Leo Rosales, a local EPA official,"so who knows where you got it."

Back home in San Francisco, I encounter a newer generationof industrial chemicals—compounds that are not banned, and, like flameretardants, are increasing year by year in the environment and in my body. Sippingwater after a workout, I could be exposing myself to bisphenol A, an ingredientin rigid plastics from water bottles to safety goggles. Bisphenol A causesreproductive system abnormalities in animals. My levels were so low they wereundetectable—a rare moment of relief in my toxic odyssey.

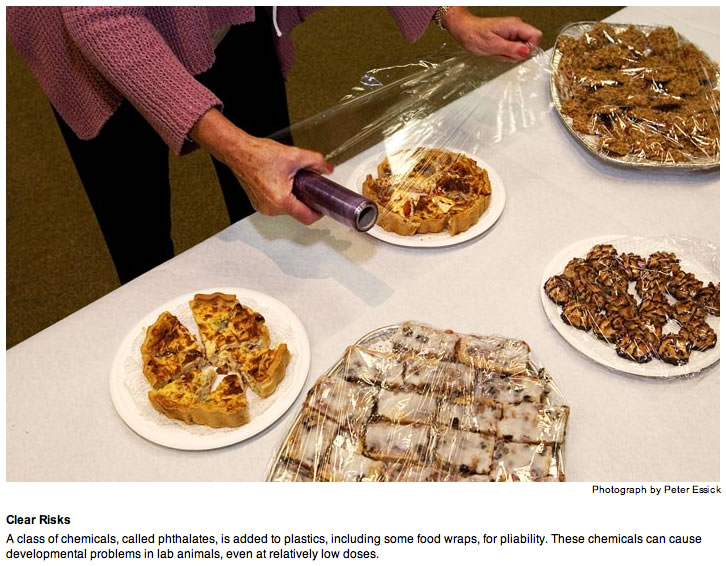

And that faint lavender scent as I shampoo my hair? Creditit to phthalates, molecules that dissolve fragrances, thicken lotions, and addflexibility to PVC, vinyl, and some intravenous tubes in hospitals. The dashboardsof most cars are loaded with phthalates, and so is some plastic food wrap. Heatand wear can release phthalate molecules, and humans swallow them or absorbthem through the skin. Because they dissipate after a few minutes to a fewhours in the body, most people's levels fluctuate during the day.

Like bisphenol A, phthalates disrupt reproductivedevelopment in mice. An expert panel convened by the National ToxicologyProgram recently concluded that although the evidence so far doesn't prove thatphthalates pose any risk to people, it does raise "concern,"especially about potential effects on infants. "We don't have the data inhumans to know if the current levels are safe," says Antonia Calafat, aCDC phthalates expert. I scored higher than the mean in five out of sevenphthalates tested. One of them, monomethyl phthalate, came in at 34.8 ppb, inthe top 5 percent for Americans. Leo Trasande speculates that some of myphthalate levels were high because I gave my urine sample in the morning, justafter I had showered and washed my hair.

My inventory of household chemicals also includesperfluorinated acids (PFAs)—tough, chemically resistant compounds that go intomaking nonstick and stain-resistant coatings. 3M also used them in itsScotchgard protector products until it found that the specific PFA compounds inScotchgard were escaping into the environment and phased them out. In animalsthese chemicals damage the liver, affect thyroid hormones, and cause birthdefects and perhaps cancer, but not much is known about their toxicity inhumans.

Long-range pollution left its mark on my results as well: Myblood contained low, probably harmless, levels of dioxins, which escape frompaper mills, certain chemical plants, and incinerators. In the environment,dioxins settle on soil and in the water, then pass into the food chain. Theybuild up in animal fat, and most people pick them up from meat and dairyproducts.

And then there is mercury, a neurotoxin that can permanentlyimpair memory, learning centers, and behavior. Coal-burning power plants are amajor source of mercury, sending it out their stacks into the atmosphere, whereit disperses in the wind, falls in rain, and eventually washes into lakes,streams, or oceans. There bacteria transform it into a compound calledmethylmercury, which moves up the food chain after plankton absorb it from thewater and are eaten by small fish. Large predatory fish at the top of themarine food chain, like tuna and swordfish, accumulate the highestconcentrations of methylmercury—and pass it on to seafood lovers.

For people in northern California, mercury exposure is alsoa legacy of the gold rush 150 years ago, when miners used quicksilver, orliquid mercury, to separate the gold from other ores in the hodgepodge of minesin the Sierra Nevada. Over the decades, streams and groundwater washedmercury-laden sediment out of the old mine tailings and swept it into SanFrancisco Bay.

I don't eat much fish, and the levels of mercury in my bloodwere modest. But I wondered what would happen if I gorged on large fish for ameal or two. So one afternoon I bought some halibut and swordfish at a fishmarket in the old Ferry Building on San Francisco Bay. Both were caught in theocean just outside the Golden Gate, where they might have picked up mercuryfrom the old mines. That night I ate the halibut with basil and a dash of soysauce; I downed the swordfish for breakfast with eggs (cooked in my nonstickpan).

Twenty-four hours later I had my blood drawn and retested.My level of mercury had more than doubled, from 5 micrograms per liter to ahigher-than-recommended 12. Mercury at 70 or 80 micrograms per liter isdangerous for adults, says Leo Trasande, and much lower levels can affectchildren. "Children have suffered losses in IQ at 5.8 micrograms." Headvises me to avoid repeating the gorge experiment.

It's a lot harder to dodge the PBDE flame retardantsresponsible for the most worrisome of my test results. My world—and yours—hasbecome saturated with them since they were introduced about 30 years ago.

Scientists have found the compounds planetwide, in polarbears in the Arctic, cormorants in England, and killer whales in the Pacific.Bergman, the Swedish chemist, and his colleagues first called attention topotential health risks in 1998 when they reported an alarming increase in PBDEsin human breast milk, from none in milk preserved in 1972 to an average of fourppb in 1997.

The compounds escape from treated plastic and fabrics indust particles or as gases that cling to dust. People inhale the dust; infantscrawling on the floor get an especially high dose. Bergman describes a family,tested in Oakland, California, by the Oakland Tribune, whose two small childrenhad blood levels even higher than mine. When he and his colleagues summed upthe test results for six different PBDEs, they found total levels of 390 ppb inthe five-year-old girl and 650 ppb—twice my total—in the 18-month-old boy.

In 2001, researchers in Sweden fed young mice a PBDE mixturesimilar to one used in furniture and found that they did poorly on tests oflearning, memory, and behavior. Last year, scientists at Berlin's CharitéUniversity Medical School reported that pregnant female rats with PBDE levelsno higher than mine gave birth to male pups with impaired reproductive health.

Linda Birnbaum, an EPA expert on these flame retardants,says that researchers will have to identify many more people with high PBDEexposures, like the Oakland family and me, before they will be able to detectany human effects. Bergman says that in a pregnant woman my levels would be ofconcern. "Any level above a hundred parts per billion is a risk tonewborns," he guesses. No one knows for sure.

Any margin of safety may be narrowing. In a review ofseveral studies, Ronald Hites of Indiana University found an exponential risein people and animals, with the levels doubling every three to five years. Nowthe CDC is putting a comprehensive study of PBDE levels in the U.S. on a fasttrack, with results due out late this year. Pirkle, who is running the study,says my seemingly extreme levels may no longer be out of the ordinary."We'll let you know," he says.

Given the stakes, why take a chance on these chemicals? Whynot immediately ban them? In 2004, Europe did just that for the penta- andocta-BDEs, which animal tests suggest are the most toxic of the compounds.California will also ban these forms by 2008, and in 2004 Chemtura, an Indianacompany that is the only U.S. maker of pentas and octas, agreed to phase themout. Currently, there are no plans to ban the much more prevalent deca-BDEs.They reportedly break down more quickly in the environment and in people,although their breakdown products may include the same old pentas and octas.

Nor is it clear that banning a suspect chemical is alwaysthe best option. Flaming beds and airplane seats are not an inviting prospecteither. The University of Surrey in England recently assessed the risks andbenefits of flame retardants in consumer products. The report concluded: "Thebenefits of many flame retardants in reducing the risk from fire outweigh therisks to human health."

Except for some pollutants, after all, every industrialchemical was created for a purpose. Even DDT, the archvillain of RachelCarson's 1962 classic book Silent Spring, which launched the modernenvironmental movement, was once hailed as a miracle substance because itkilled the mosquitoes that carry malaria, yellow fever, and other scourges. Itsaved countless lives before it was banned in much of the world because of itstoxicity to wildlife. "Chemicals are not all bad," says ScottPhillips, a medical toxicologist in Denver. "While we have seen somecancer rates rise," he says, "we also have seen a doubling of thehuman life span in the past century."

The key is knowing more about these substances, so we arenot blindsided by unexpected hazards, says California State Senator DeborahOrtiz, chair of the Senate Health Committee and the author of a bill to monitorchemical exposure. "We benefit from these chemicals, but there areconsequences, and we need to understand these consequences much better than wedo now." Sarah Brozena of the industry-supported American ChemistryCouncil thinks safeguards are adequate now, but she concedes: "That's notto say this process was done right in the past."

The European Union last year gave initial approval to ameasure called REACH—Registration, Evaluation, and Authorization ofChemicals—which would require companies to prove the substances they market oruse are safe, or that the benefits outweigh any risks. The bill, which thechemical industry and the U.S. government oppose, would also encouragecompanies to find safer alternatives to suspect flame retardants, pesticides,solvents, and other chemicals. That would give a boost to the so-called greenchemistry movement, a search for alternatives that is already under way inlaboratories on both sides of the Atlantic.

As unsettling as my journey down chemical lane was, it leftout thousands of compounds, among them pesticides, plastics, solvents, and arocket-fuel ingredient called perchlorate that is polluting groundwater in manyregions of the country. Nor was I tested for chemical cocktails—mixtures ofchemicals that may do little harm on their own but act together to damage humancells. Mixed together, pesticides, PCBs, phthalates, and others "mighthave additive effects, or they might be antagonistic," says James Pirkleof the CDC, "or they may do nothing. We don't know."

Soon after I receive my results, I show them to myinternist, who admits that he too knows little about these chemicals, otherthan lead and mercury. But he confirms that I am healthy, as far as he cantell. He tells me not to worry. So I'll keep flying, and scrambling my eggs onTeflon, and using that scented shampoo. But I'll never feel quite the sameabout the chemicals that make life better in so many ways.