Originally printed in the National Geographic Magazine - July, 2005

There are a number of places in the Rocky Mountains today where you will find the Old West grinding against the New, and Pinedale, Wyoming, is surely one of them. A quiet, Main Street sort of town (population 1,500) tucked behind a mesa in the sagebrush valley of the upper Green River, Pinedale is known as the home of the Museum of the Mountain Man. And this stretch of the Green is famous as the site of the riotous rendezvous that drew those buckskinned adventurers here in the waning summers of the fur trade. From hills roundabout you can see in the east the snow-dusted peaks of the Wind River Range, and the faraway Wyoming Range to westward.

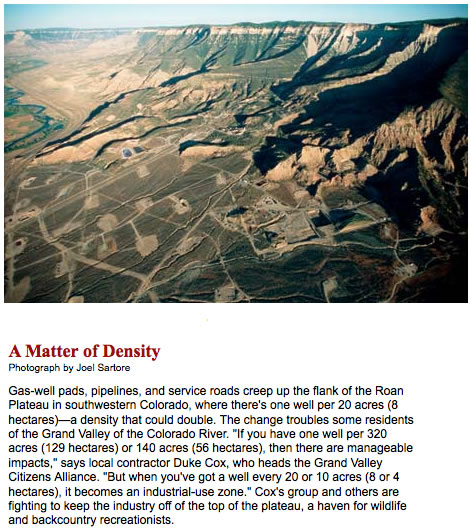

This is vintage Old West scenery you're looking at. Soak it up while there's still a chance, for that other West, the New West of pipelines, thumper trucks, and drilling rigs, sits up there on the mesa and southward beyond it. To take its full measure, this West is best observed not on the ground but from the window of a single-engine plane, circling what some people regard as an environmental killing field, while others embrace it as one small but crucial platform on the path to our nation's energy independence.

Airborne, on intercom, I have Linda Baker of the Upper Green River Valley Coalition and Bruce Gordon of EcoFlight, our pilot out of Aspen, Colorado. Over the years Gordon has logged hundreds of thousands of air miles giving lawmakers and journalists the bird's-eye view of land-use battlegrounds. Now, near the Pinedale mesa's north end, Gordon is circling a place called Trappers Point, a bluff dropping off to the Green River. A scant half mile of open country is all that separates the point from a rural subdivision hugging the highway to Jackson.

"There's the bottleneck," Baker is saying. "That's one of the places the pronghorn and mule deer have to squeeze through on their migration from summer range in Teton National Park into the upper Green."

The U.S. Bureau of Land Management controls the rights to natural gas around Trappers Point, and it is uncertain when, or whether, the agency will lease it for energy development. But even if the BLM refrains from leasing the point, the migrating ungulates—sometimes numbering in the thousands—face a daunting challenge as they press farther south into their winter range. It happens that the Pinedale mesa not only sits athwart the migration corridor but also overlies the Pinedale anticline, a sandstone formation containing trillions of cubic feet of natural gas. Seven hundred wells have already been approved on the mesa, and 230 are now in production. The gas fields are laced with about a hundred miles of access roads and pipelines. And as we fly south beyond the mesa, we can see the more tightly spaced well pads of the Jonah field, with 500 more wells in place and the BLM proposing to increase that number by 3,100.

"This is a national sacrifice area," Baker says over the intercom. I had heard it described from a different perspective just the day before at the Pinedale office of the BLM: "In terms of productivity, there are few onshore gas fields equal to the Jonah in the lower forty-eight," said Prill Mecham, the BLM field manager.

Heading back to the airstrip at Pinedale, Gordon says, "This is just the tip of it. I can fly one hour in practically any direction in the Rocky Mountains and look down and see some sign of oil and gas development. They're going for it almost everywhere."

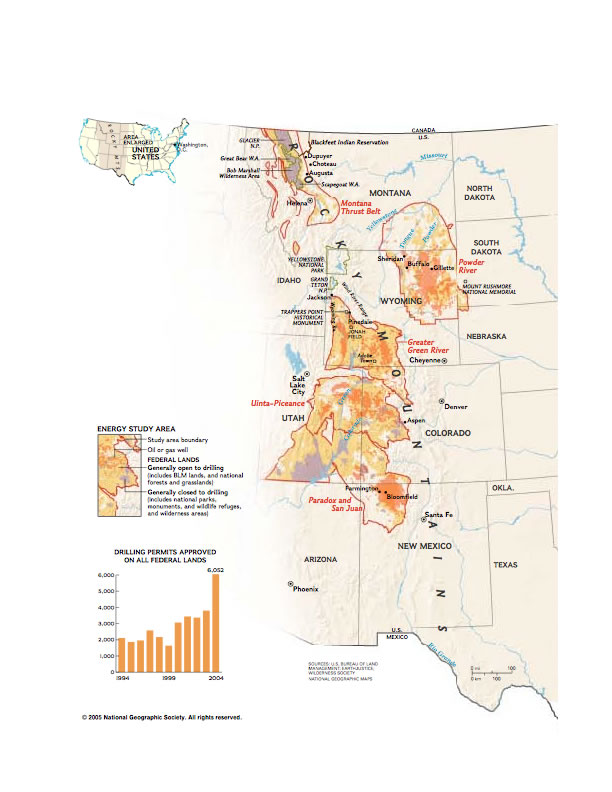

Gordon's perception of "almost everywhere" is not quite the same as that of the energy industry or the U.S. Geological Survey, the official arbiter of where our fossil fuel riches lie. For extracting natural gas, the Survey has identified five promising regions in the Rocky Mountains, including Wyoming's Greater Green River Basin. They range across 60 million acres managed by the federal government, plus millions of acres of state and private land, from New Mexico north to Montana. Within those five regions the federal lands alone are said to contain enough "technically recoverable" gas to supply current U.S. demand for six years.

That bit of industry jargon is an important qualifier, for it means that while the technology exists to get the gas out of the ground, actually doing so may be prohibitively expensive. What's more, drilling advocates and their opponents still debate exactly how much of this gas might be available for development. The Bush Administration's 2001 National Energy Policy report claimed that about 40 percent of natural gas resources on federal land in the Rocky Mountain region is off-limits due to land-use restrictions or environmental safeguards. Yet opponents cite a 2003 joint study by the Interior, Energy, and Agriculture Departments that found only 12 percent of the resource unavailable for leasing. Or, as some would sum up the situation, 88 percent is up for grabs.

Another issue: On BLM land nationwide, drillers are working fewer than half the leases they already hold. A study by the Wilderness Society, for example, estimates that of the 45,836 oil and gas leases supervised by the BLM, more than half were not producing as of last February. So what has been fueling the drive to poke new holes into the well-punctured crown of our continent when there already appears to be a surfeit of untapped leases? Some energy analysts attribute it to the slow pace of domestic production in recent years, which, coupled with increased demand, pushed up the price of natural gas. Then, of course, there is the environmental advantage that gas, which burns cleaner than coal, holds over its grimy fossil cousin.

And finally there was and is the Bush-Cheney energy plan, drafted behind closed doors by a vice president and other insiders with private-sector résumés reeking of petroleum. Out of this plan emerged the White House Task Force on Energy Project Streamlining, conceived as a kind of ombudsman to sort out the differences between an impatient industry and red-taped federal agencies, but which in practice functioned as a complaint desk for companies seeking faster access to gas fields and other resources. BLM managers throughout the Rockies received their marching orders in August 2003 when the agency issued a directive urging them to remove unnecessary restrictions on energy development and expedite the processing of drilling applications. This, BLM director Kathleen Clarke said, "will further our agency's efforts to ensure a reliable supply of affordable energy, as called for by the President."

It was the unfolding of these plans and policies, and the outcry against them—often by unlikely coalitions of ranchers, hunters, outfitters, and environmental activists—that drew me last year to western battlegrounds where massive drilling threatens to change dramatically the character of unspoiled lands.

The Powder River Basin

Throughout the Rocky Mountain region, the energy industry is mostly producing two kinds of natural gas: tight sands gas, found in sandstone formations, and coal bed methane (CBM), trapped in seams of coal. The Powder River Basin of northeastern Wyoming and southeastern Montana is methane country. But while the cost of drilling to reach CBM is less expensive than tapping deeper sandstone formations elsewhere, the cost of extracting it can be pricey. To release and collect the gas, drillers must first pump out the groundwater that holds the gas under pressure within the coal seams. Then the operator has to dispose of the water, often tainted with elevated levels of salinity.

As we toured some of the gas fields near Sheridan, Wyoming, Jill Morrison of the Powder River Basin Resource Council, a group that represents farmers, ranchers, and other rural residents, explained why the CBM wastewater has become such a problem. "For one thing," she said, "the sheer quantity is staggering. We're talking billions of gallons of water. On these clay soils here, you can't safely irrigate with it. The salinity has a negative effect on crops and native vegetation." Some in the gas industry and a few irrigators, however, treat the wastewater to make it usable.

A day earlier I had dropped by the BLM office in Buffalo, Wyoming, which oversees much of the state's Powder River Basin, and spoken with Richard Zander, associate field manager. Last year this office, with more than half its staff of 80 assigned to minerals management, received a special commendation from Washington for issuing more new drilling permits than any other BLM office in the country. Some 18,000 wells are in place now, and 14,000 of them are producing about a billion cubic feet of gas daily. Another 35,000 wells are projected over the next six years.

Zander conceded there is an issue with the water and how to get rid of it. Much of it goes into evaporation pits or reservoirs, and occasionally, I was told by Morrison and others, there have been overflows into nearby watercourses, including the Tongue River. But against that downside, Zander cited benefits accruing to landowners. Most of the mineral rights in the basin are held by the BLM, the state, or individuals other than the residential and ranching folks who "own" the surface. Zander said "nuisance fees" are paid to the surface owners by most energy companies, as much as $2,000 for the first year of the life of a well pad, and $1,000 a year thereafter, plus smaller sums for road and pipeline access. "For a large rancher, that could add up to $30,000 a year—and that's just gravy."

But there's another kind of gravy in Powder River country. It is the sludge that can come out of a homeowner's tap when CBM drillers de-water the aquifer feeding that homeowner's well and cistern. Consider the case of Allison and Richard Cole, who believed they had found their American dream in a comfortable five-bedroom house on high, open, rolling prairie ten miles north of Sheridan. "The wild, wonderful West just opened up to us," said Allison Cole. But soon their home and those of five other families were sitting within a horseshoe of two dozen CBM wells pumping methane and water from a formation known as the Anderson coal seam.

"We lost our water in April 2003," Allison Cole told me. "By August 2004, five other houses here had lost their water too. The drilling company, J.M. Huber Corporation, told us, 'The reason you have no water is that your well pump burned out.' And I said, 'Yeah? And the reason the pump burned out is because it had no water.'"

"It takes away the joy of living out here on the prairie," said Richard Cole. "We'd just like to get out of here now." And Allison added: "But we can't even put the house on the market. Who wants to buy a house without running water?"

A Huber spokesman said there is "no evidence" that the well failures have been caused by drilling activities. He cited other possible factors such as the region's lengthy drought and increasing residential development in the area. As part of what it calls its "Good Neighbor" policy, Huber refills the Coles' and other cisterns weekly with trucked-in water, and it has proposed constructing a replacement water supply system for all the affected landowners.

The Front

By most accounts, nothing can match Montana's Rocky Mountain Front for its capacity to inspire awe—for the striking visual quality of its primitive landscapes, for the biological integrity of its layered habitats, and for its ark-like concentration of charismatic critters. From the edge of Glacier National Park and the Blackfeet Indian Reservation on the north, the escarpment of the Front sweeps south a hundred miles, past the Badger–Two Medicine wildlands held sacred by the Blackfeet; past the eastern spires of the Great Bear, Bob Marshall, and Scapegoat Wilderness Areas; past wildlife refuges and natural areas administered by the Forest Service, the BLM, or the state. This is what the Blackfeet call "the backbone of the world." Westward of the high-plains hamlets of Augusta, Choteau, and Dupuyer, grasslands roll out to collide with ponderosa foothills and the mountain battlements that loom above them. There are grizzlies here. There are black bears and cougars and wolves. There are moose, elk, mule and white-tailed deer, pronghorn, bighorn sheep, mountain goats, lynx, wolverines, eagles, hawks, owls. But underlying these wild places and wild species are scores of inactive oil and gas leases. Some of these leases, though currently on hold by the BLM, could be opened for production as early as 2008, should the Bush Administration decide to do what it was ready to do, but didn't, just a few years earlier.

On the deck of a ranch house west of Dupuyer, with the blue-gray wall of the Front rising in the distance, I spent part of a morning talking with rancher Karl Rappold—his eyes reflecting that high-plains squint that seems to come with the territory, a full, thick mustache not quite muffling the passion in his voice as he spoke of this ranch that his grandfather first homesteaded in 1882.

"I'm just the caretaker here," he said, sweeping his arm over the plains rolling toward a rumpled mountain called Old Man of the Hills. The ranch now spreads over 7,000 acres, but Rappold leases 6,000 more from neighboring landowners. One section reaches right up the Front to touch the edge of the Bob Marshall Wilderness. With such a spread, you'd think a cattleman might be running a herd of several thousand head. Rappold runs 350 Angus. "Got to leave some feed for the deer and the elk," he said. "And the grizzlies. They come down here too. We've seen two big boar grizzlies, thousand pounds each one of them. Those big old devils been wild and free all their lives, and they're going to stay that way. This is their last stand. Right here." To help assure that, Rappold—much to the dismay of some other ranchers roundabout—has placed some of his land under conservation easements held by the Nature Conservancy and the U.S. fish and Wildlife Service.

For the time being, much of the Rocky Mountain Front would seem to be secure against any prospect of energy development. Rappold himself owns the mineral rights under his land, although if active leasing were to go forward on neighboring lands, federal condemnation proceedings could force him to provide something almost as unwelcome as drill pads—pipeline and vehicular access to the neighbors' wells. Nor could Rappold ignore memories of the recent battle of Blindhorse canyon, in the foothills southwest of his ranch. A Canadian energy company was poised to sink some wells in that canyon, despite editorials deploring the project in major newspapers across Montana. The BLM, seeking public comment, received nearly 50,000 letters and e-mails, 99 percent of them opposed to drilling. What surely helped trigger that rebuff was a growing awareness that outdoor recreation, even more than ranching, might hold the key to the region's economic future. Concerns for quality hunting and fishing, and for the vitality of local businesses that cater to the needs of outdoorsmen, are not easily dismissed in western Montana. Many ranchers supplement their incomes by serving as outfitters or guides, packing hunters into the backcountry.

On the eve of the presidential election last November, the BLM placed a stop order on its study of the Blindhorse proposal and announced it would approve no new energy activity along the Front until after a "landscape level" review is undertaken in 2007. That is the same year in which a Clinton-era moratorium on leasing in the Front's Lewis and Clark National Forest could be lifted by the Bush Administration.

The San Juan Basin

Among Anglo Americans in the Rocky Mountains, you won't find many with roots running deeper than Linn Blancett's. His cross six generations, all the way back to that first Blancett who came to the Rockies to open a trading post and founded a family line that, after a spell of ranching in Colorado, would drive its cattle south into this sere northwestern corner of New Mexico. A hundred years ago Blancetts were running more than 600 head in San Juan County. Now, on 32,000 acres of grazing land, most of which they lease from the BLM, Linn Blancett and his wife, Tweeti, are running no herd at all. They sold off all but a few of their cattle late in 2003, informing the BLM that they could no longer ranch effectively because of the agency's failure to enforce regulations governing the 450 wells that pepper their spread. The wells and their associated compressors, pipelines, and access roads, Linn Blancett contended, had caused unmitigated erosion, loss of forage, and pollution of both air and water.

"We understand today as in the past the need to drill," Blancett wrote in a letter last year to Steve Henke, who runs the BLM district office in Farmington. "What we don't understand or accept is the destruction of our ranches in the process."

Steve Henke, for his part, acknowledges that drilling for natural gas in the San Juan Basin is having some impacts; he just doesn't see them being as serious as Linn Blancett does. "I cannot agree with those who say that ranching is no longer viable here," Henke told me. "We're doing everything we can to keep them in business, because ranching is not what they do—it's who they are."

Despite Henke's assurances, several lawsuits are currently wending their way through the courts. One, filed against the BLM and Interior Secretary Gale Norton by three chapters of the Navajo Nation, the Natural Resources Defense Council, and Tweeti Blancett, among others, challenges a plan to authorize nearly 10,000 new oil and gas wells in the San Juan Basin over the next 20 years. Another legal action targets Burlington Resources and two other basin producers, alleging hazardous waste spills. Burlington, the basin's most active producer, holds down a big office in Farmington employing 280 people. The man in charge there is vice president Richard Fraley. In our conversation and in a prepared statement later posted to me, Fraley said he believes that the "vast majority" of Burlington's operations "fully comply with applicable federal, state, and local regulations at any given time." The company spends about 240 million dollars annually on goods, services, and salaries in the Farmington area. And Burlington is one of the largest payers of state income and royalty taxes in the state of New Mexico.

"The bottom line," said Fraley, "is that, unlike the Blancetts, the vast majority of ranchers are pretty happy with what we've been doing here."

Linn Blancett figures he knows the reason. "Farmington is a company town," he said. "I hardly know of a ranching family that doesn't have somebody working for or servicing an oil company. This is the employment base." By some accounts, the happier ranchers are those who can look forward to substantial mineral-rights royalties and other industry payments to offset their ranching losses.

Trappers Point

I had come to Pinedale, Wyoming, to check out that wildlife migration corridor across the Pinedale mesa, but had seen it only from the air. Now I wanted to have a look at that special place called Trappers Point, this time with my feet on the ground. I also needed to check out reports that at least one energy company was trying to minimize the impact of its drilling. So I called on Ronald E. Hogan, general manager of Questar Market Resources, a Utah firm that has been poking into the Pinedale anticline for 40 years. Questar operates 106 wells up on the mesa. It is aiming to have 350 more in place before 2012. "You know," he said, "there's 20 trillion cubic feet of gas in that anticline. That's enough to supply the entire United States for a year."

Hogan explained how Questar was trying to work out an agreement with the BLM that would allow the company to expand its drilling during the winter months. At the time, most drill rigs, heavy equipment, as well as the public at large were barred from the mesa November to May to avoid disturbing the wildlife. But Hogan argued that lifting some winter restrictions would let Questar employ a technology called directional drilling, by which a single drill rig can tap distant gas deposits. This would allow the company to reduce the number of projected new drill pads, cut the duration of its drilling operations on the mesa from 18 to 9 years, and improve the economic stability of the community by keeping its workforce dependent on local services year-round, instead of seasonally. (Several months after our tour of the mesa, the BLM approved Questar's proposal when it issued a "finding of No Significant Impact.")

Leaving Hogan's Pinedale office, I pulled off the highway where a small sign pointed the way to Trappers Point Historical Monument. At the top of a steep dirt track, posted inside a small enclosure, the stenciled legend on a marker set the scene. "Along the river banks below are the Rendezvous sites of 1833, 1835, 1836, 1837, 1839, 1840. . . . Trappers, traders and Indians from throughout the west here met the trade wagons from the east to barter, trade for furs, gamble, drink, frolic, pray and scheme." But the legend says nothing of how the beaver trade, the first great exploitation of the West, ended in the campfire smokes of that last rendezvous. By 1840 the beaver had been virtually extirpated from the mountains, trapped out at the rate of 100,000 a year. On the boulevards of New York and Paris, dandies would be doffing a new kind of hat. It was made of silk.

It's said that the Pinedale anticline could be producing until 2040, at which point the recoverable gas will probably be gone. What a timely but poignant end to it that would be. Standing there above the Green River, I imagined the Museum of the Mountain Man getting all decked out to observe the bicentennial of the last rendezvous. Perhaps the city fathers would be opening a new exhibit: the Museum of the Fossil Fuel Man. Who was that wise scholar who once said that the only thing we learn from history is that we learn nothing from history?